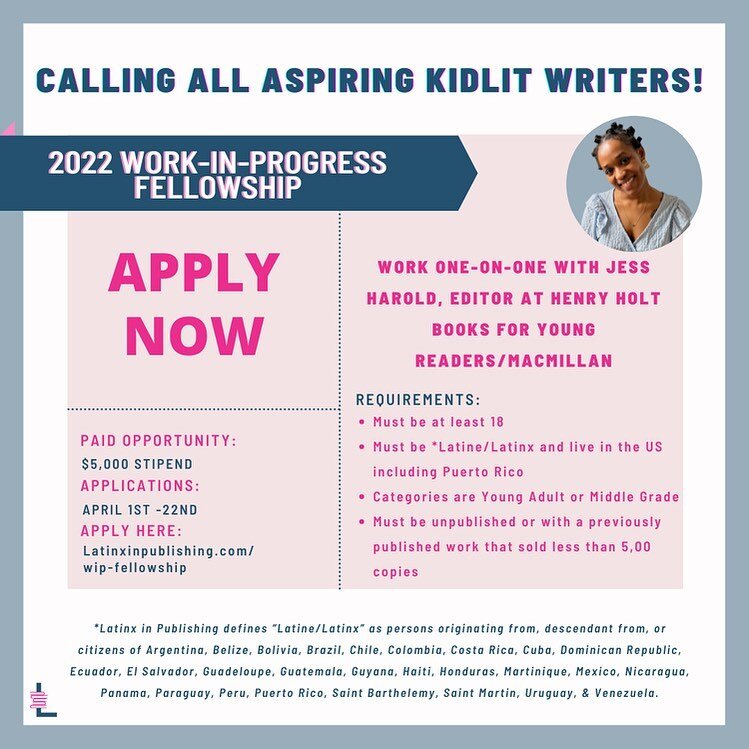

Latinx in Publishing is very excited to partner with Macmillan Publishers to bring you an exclusive excerpt from Craft: Stories I Wrote for the Devil (on sale June 18, 2024), written by inaugural Work-In-Progress fellow, Ananda Lima. Keep reading below for an exclusive sneak peak!

TROPICÁLIA

I’m only interested in what is not mine.

—Oswald de Andrade, The Cannibalist Manifesto, 1928

Fred, what we want is, I think, what everyone wants, and

what you and your viewers have—civilization . . . We want

to be civilized.

—Brain Gremlin, Gremlins II: The New Batch, 1990

Sunday, August 20 🌘 Waning Crescent

(Day minus 1)

I woke from unsettling dreams to my mattress jingling with loose change. I lay on my stiff back, armor-tight with tension. I raised my head a little and saw my brown belly divided into sections, striped by the sun slicing through half-open vertical blinds. The lines extended and covered the room with bars. With a monstrous hangover, I peeled off a penny stuck to the skin next to my belly button, then remem- bered my passport.

I stood up too quickly and shielded my right eye from a beam of sunlight. Wincing at something hard digging into the sole of my foot, I looked down and saw I stepped on my treasured Gremlins key chain, fracturing my poor Gizmo’s tiny plastic back. I was sweating. I closed the blinds. Part of my nightmare returned (sun, salt, me with an insect’s legs, scurrying south on city streets).

My phone hid in my papers on global localization strategies (I worked with semiautomated corporate translation), betrayed only by its limp cord, hopelessly disconnected from a power source. Reflected on my dead screen, I looked like vermin. A dream, I reminded myself, and plugged in the phone. As I waited, I stood up and readjusted a crooked white framed triptych of a winking Pop Art Carmen Miranda, her three heads heavy with fruit. The screen turned on and I wiped away the notifications. No missed calls. No emails from work. My nausea gathered and condensed into a singularity in my stomach. That part had not been a dream. No messages about my missing passport. My passport, holding my H-1B work visa, was gone.

Sunday, August 13 🌖 Waning Gibbous

(Day minus 8)

I was having Cheerios for lunch on the shelf I IKEA-hacked into a counter in my kitchen, which was also my living room. I’d worked late on an analysis of our human translator testers the night before. It had gone well, and I was excited about what I might bring to my boss, Meredith, the following week. But I had overdone it and needed a break. So I spent most of my Sunday morning on Pinterest. My prewar studio impersonating a one-bedroom apartment was not as I wanted it yet, but getting there. The view was still water towers on this end and a dumpster on the other. But I had an exposed brick wall, tropical plants, including a monstera, a berimbau I couldn’t play. Though I hadn’t found anything on Pinterest that day (a bad sign).

I swiped out of the news Google had selected for me (rumors of raids in Queens, seven steps to boost your career, tips for watching the Great American Eclipse), then checked there were no emails from work. I needed to stop thinking about work (it had become even harder since Meredith mentioned a possible promotion). On the Brasileiros de Nova Iorque group, a post advertising a facial had three likes. Seven likes on a picture of a Minnie Mouse cake surrounded by brigadeiros. And 137 combined sad faces, angry faces, thumbs-up, at least one laughing emoji, and fifty comments on a post by a woman thinking about divorce but afraid for her green card application. The top comment began, “I get that there are many out there that don’t respect the law. But if you choose to do things right (like I certainly do), there are only two ways: it’s either a real marriage or an employer sponsors you. Now if you choose not to educate yourself, not to work hard, or . . .”

I stopped reading, startled by something moving on a spoon on the counter, just under where I was holding the phone. I thought it was a cockroach but realized the dark lump trapped at the center of the spoon had been my reflection. I heard a buzzing coming from the window. There was a fly there, trapped between the glass and the screen. I didn’t want to kill it per se; I just wanted it gone. So I looked for help on YouTube, which led me to The Fly, a movie I hadn’t seen since I was a child. I watched it instead of dealing with the real fly, and that was my Sunday. Nothing else happened, but the comments from the Brasileiros de Nova Iorque group stayed with me the whole day and through the night.

Monday, August 14 🌗 Last Quarter

(Day minus 7)

That Monday, I missed my alarm and woke up late at eight thirty. I got ready in a panic. When Meredith had told me about a position opening up and briefly mentioned this one guy as my competitor, I’d imagined some guy in a skinny suit, with gelled hair and pointy, overly shiny brown leather shoes. I imagined him in the mirror, shaking his head at me as I hurried to brush my teeth. The position had to be mine. There were the usual things: yes, career, I needed more money. But mostly, I was entering the last year of my H-1B visa and needed to ask the company to sponsor my green card, as they had vaguely alluded to when I’d been hired.

I was about to leave but paused at the threshold of my open front door. I sent a message to Meredith, apologizing for running late. I told her there was trouble on the F line and that I would be there as soon as I could. Then I went back in and sat on my green velvet couch. I opened the Brasileiros de Nova Iorque group and scrolled through the posts on the president’s tweets, the eclipse, and microblading. The woman wanting a divorce seemed to be gone. But I wasn’t after her. I kept scrolling until I found the ICE thread. Those who had passports, visas, and green cards were arguing about whether to always carry them (“I thought that was just an Arizona thing,” “How will they be able to tell,” “In 25 years nobody has ever,” “Well, they asked me,” “If you have nothing to hide”). Of course, the rule didn’t fully make sense, as a Brazilian guy who appeared white in his profile picture had pointed out in the group. If they stopped noncitizens to check their papers, wouldn’t they have to stop citizens as well? How would they know whom to stop? It wasn’t like noncitizens put stickers on their lapels indicating noncitizenship. He reminded me of the guy in the studio control room in Gremlins 2, mocking the logic of the “don’t feed after midnight” rule, speculating what would happen to a gremlin crossing time zones. As he begins to laugh at his own jokes, a gremlin springs up and eats his face.

There it was, right after the comment on rumored ICE activity on the 7, the USCIS link. I clicked. The open-armed blue-and-white eagle greeted me in its familiar unnerving way. I read the passage (“every alien,” “at all times,” “personal possession,” “alien registration,” “comply,” “guilty,” “fined,” “imprisoned,” etc., etc.) again. Yes, supposedly, it applied to all of us. Anyone not considered a citizen had to be ready with the applicable papers. At all times.

I thought of my opponent for the promotion again. I imagined him thin, with a sharp jawline, blue eyes, black hair, walking into our building, taking confident sips of his morning kale smoothie. Fresh and ready for action, having started his day with yoga or spinning or both. I imagined Meredith’s boss, Mr. Koning, and his lot of higher-ups nodding to one another in approval. They’d notice a commotion in the background, turn, and see me being shoved into a van while trying to appear professional in a pencil skirt. Handcuffed, I’d still wave meekly at Meredith, who would admit, embarrassed, that the woman being taken away by the authorities was the candidate she’d suggested for promotion.

I went back in for my passport, safely cocooned in a ziplock bag, inside a shoebox, under my bed. I opened the H-1B stamp page, hovered my fingers over my picture, the signature, the seal, just short of touching it. I closed the passport and put it inside a compartment in my respectable brown leather Banana Republic outlet bag and zipped it, then closed and buttoned the top flap.

On the train to work, I let go of the pole momentarily and searched for any new posts about H-1Bs on the Brasileiros de Nova Iorque group. I grabbed the pole again and clicked with my free hand on the link someone had posted of a forum that crowdsourced updates from applicants for various visas and calculated current processing times. But I lost reception before it opened. I had looked at the forum repeatedly and most likely wouldn’t have found anything new, but I couldn’t stop checking.

I swapped the hand holding the pole, brushed lightly against the hand of a blond woman, and apologized. She looked straight ahead. A message from Meredith popped up on my screen: “Everything is fine over here.” Luckily, I was not meeting her first thing in the morning. And I still had a small buffer before the meeting with the translators. “I’m so sorry,” I texted Meredith. I took a deep breath and went over the plan for the translators meeting again. I would walk to their backroom, the same room where I’d worked when I first joined, then have them leave their cubicles and sit with me in a circle over cookies and coffee. Nothing formal. I would remind them again of how I had started just like them. How Marisa had helped me find everything on the first day of work, how Miki had stopped me from accidentally entering the men’s bathroom. Then I would pivot to introducing the basics of the new rewards system. Not all the details on the points this time. I just hoped they understood the opportunity available to each of them. If only they could see it. I was lucky to have had Meredith help me. Maybe I could do the same for one of them. After the meeting, I’d go over the new targets with Meredith. I knew we could increase the output on our end if we just tightened the ship a bit. I was also thinking of a new metric, a simple addition requiring translators to rate the work of their colleagues as it moves through the workflow. It would be a chance for them to get more credit when they worked hard. And it would address our concern about individual accountability. Meredith would love it.

The train sped up. A white man in a suit reached for our pole, squeezing by a Latino man wearing jeans and work boots, who reminded me of somebody, though I couldn’t tell whom. The blond woman sighed. I counted the five hands sharing the pole, including a woman—brown like me, but with electric-blue nail polish—who just managed to grab it with her fingertips. I couldn’t see her face. Across the car, I spotted a muscular white man with a crew cut, dark gray pants, and a black polo shirt, sitting on one of the orange seats. A photograph from the Brasileiros de Nova Iorque group sprung to my memory: men in black shirts and sunglasses, “ICE” written on white letters on their backs. Without thinking, I ran my hand over the pocket carrying my passport. I wished I could get to work.

I realized the man reminded me of Jeff Goldblum, which was strangely reassuring. I thought of The Fly. Brundle’s tragic and hilariously gross journey from scientist to giant fly. His skin smooth, then stubble, then blisters, then gooey raw meat. All done in analog in 1986. The whole thing had to do with movement, teletransportation, which fascinated me. He entered a pod a normal guy. He couldn’t see it, but by the time he stepped out of the other pod, he’d already become a monster.

As the doors finally slid open at my stop, another message from Meredith arrived: “Don’t worry about a thing.”

Sunday, August 20 🌘 Waning Crescent

(Day minus 1)

The passport lasted less than a week being carried everywhere in my bag. There were a couple of times when it felt right to have it there, close to me. That one time in the subway; that afternoon walking under the rows of American flags, by the rows of police (or military or both) at Penn Station; that time going through the security desk and turnstile when I joined Meredith for a client meeting in a different building. But mostly, there was the fear I would lose it. It was like being resigned to having a fly trapped in a room: Sometimes you forgot it was there, and then it came back buzzing, and you had to wait until it stopped and you forgot it again.

And now here I was. Two caplets of Tylenol, a mug of water, and my phone lay on my imitation-marble coffee table. I called the Mandarin Hotel bar. I balanced my phone between my head and my shoulder as I waited, squeezing the sides of my broken Gizmo key chain as if trying to undo the split along its back. With the back open, its head no longer stayed firmly in place. Nobody answered at the bar. I tried the main hotel, where the receptionist informed me the bar opened at four. I thought of the USCIS passage (“alien,” “at all times,” “personal,” “possession,” “guilty”), sitting among the other words on their site all this time. And the same text in dusty books before there was such a thing as a USCIS website, the letters set in bookshelves while I played in our muddy backyard in Brazil, my cousins laughing as I imitated ALF’s dubbed Portuguese voice. And the same words on other shelves somewhere in the US before that, long before I’d been born.

I put up my broken Gizmo up on my bookshelf, next to a sad baby banana seedling I’d ordered online, its two little leaves wilted and browned. The shelves were full of classics I hadn’t read. A few titles in Portuguese (Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas, A Paixão Segundo G.H., O Estrangeiro), the rest in English. Part of an effort to convey that I am a particular kind of person I couldn’t have pretended to be back in Brazil. An ambition that is only possible because Americans don’t know what my accent in Portuguese, or my name, or my parents’ names convey about our place in the world.

Gizmo’s head fell off and rolled close to the edge of the shelf, butI caught it right before it dropped and carefully placed it next to itscracked headless body. At the vintage store where I’d found it my first year in the US, there had been a couple in mismatched plaid shirts ahead of me in line who saw the key chain first. They looked at it with mild interest and put it back. When the woman said the word “gremlins,” it took a second for my brain to map the word as she pronounced it to the way the word had lived in my head as a child. We said “gremilins” in Portuguese, that extra i added like a drop of water to the back of a mogwai, giving rise to an additional syllable. When I realized the key chain was Gizmo, I reached for it immediately. I estimated how many times I’d watched Gremlins 2 in Sessão da Tarde reruns in Brazil. Every afternoon I ate lunch with my brother and sister and watched the soap operas. After the novelas came the few movies TV Globo had dubbed in Portuguese. The same recognizable voices regurgitated out of the mouths of different actors, over and over in all the movies they showed. How strange to feel at that moment that the little Gizmo was more rightly mine than theirs, that American couple who’d clearly missed the movie’s brilliance.

I pushed the broken pieces back, farther into the shelf, to make sure they didn’t fall, and went to get ready to leave.

Saturday, August 19 🌘 Waning Crescent

(Day minus 2)

I last checked on my passport late Saturday afternoon, just before I walked out with Meredith. She had found a way to bring me along for drinks with Mr. Koning, her boss. As I’d been about to leave work the previous day, she had held my shoulders, looked me in the eye, and told me the timing was perfect. I had been giddy about it all afternoon, but now I was worried about what I was supposed to do, about not messing up my great chance. We were at an exclusive spot at the Mandarin Hotel. A place just like I’d imagined people like them went: a little Mad Men, somewhere along a lineage of leather Chesterfields, dark wood, and shelves filled with matching book covers, seamlessly mixed with dark mid-century furniture. And those floor-to-ceiling windows again. Here the city appeared brighter and closer. It felt as if the people in the other buildings could see everything and everyone, including me. It felt familiar, though I had never been there. A déjà vu. I couldn’t place it, and that made me more nervous. I ordered a Malbec.

I sipped it quietly as they discussed projects outside my department. Meredith alternated her posture: sometimes sitting back and propping her elbows on the back of the chair, grabbing her whiskey on the rocks in the relaxed “I don’t care” manner of Mr. Koning and other seemingly powerful men in the restaurant; sometimes sitting up, cross-legged, her arms close to her body as if trying not to occupy space; sometimes leaning into the table and touching her hair, almost flirtatiously. Mr. Koning didn’t notice how she advanced and retreated strategically, slowly gaining space. She indulged all his interruptions and came back around in a gentle way, until her points were made. Even after everything Meredith had taught me and what I’d learned by watching her, there was so much more. I was struggling to find an opening. I realized I was hiding behind my wineglass, not varying my posture, not saying anything. Mr. Koning didn’t seem to notice me. I put my glass down and leaned into the table slightly, bending toward him. I decided my focus now would be to appear fascinated by whatever he said (which was?). I knew Meredith would manage to bring me into the conversation in a manner that was most advantageous to me. I waited for her cue. She always looked out for me.