Dariel Suarez was born in Havana, Cuba, and immigrated to the United States with his family in 1997. His debut story collection, A Kind of Solitude, received the 2017 Spokane Prize for Short Fiction and the 2019 International Latino Book Award for Best Collection of Short Stories. Dariel is an inaugural City of Boston Artist Fellow and Education Director at GrubStreet. His prose has appeared in numerous publications, including the Threepenny Review, Prairie Schooner, the Kenyon Review, and the Caribbean Writer, where he was awarded the First Lady Cecile de Jongh Literary Prize. Dariel earned his MFA in Fiction at Boston University and currently resides in the Boston area with his wife and daughter.

I met Dariel during my time as a Marketing and Media intern with Red Hen Press. His debut novel, The Playwright’s House, immediately caught my eye because of the mystery and enlightening look into life in Cuba during the Special Period. We had the wonderful opportunity to speak with one another about the inspirations for his novel, writing advice for young Latinx writers, and his passion for music.

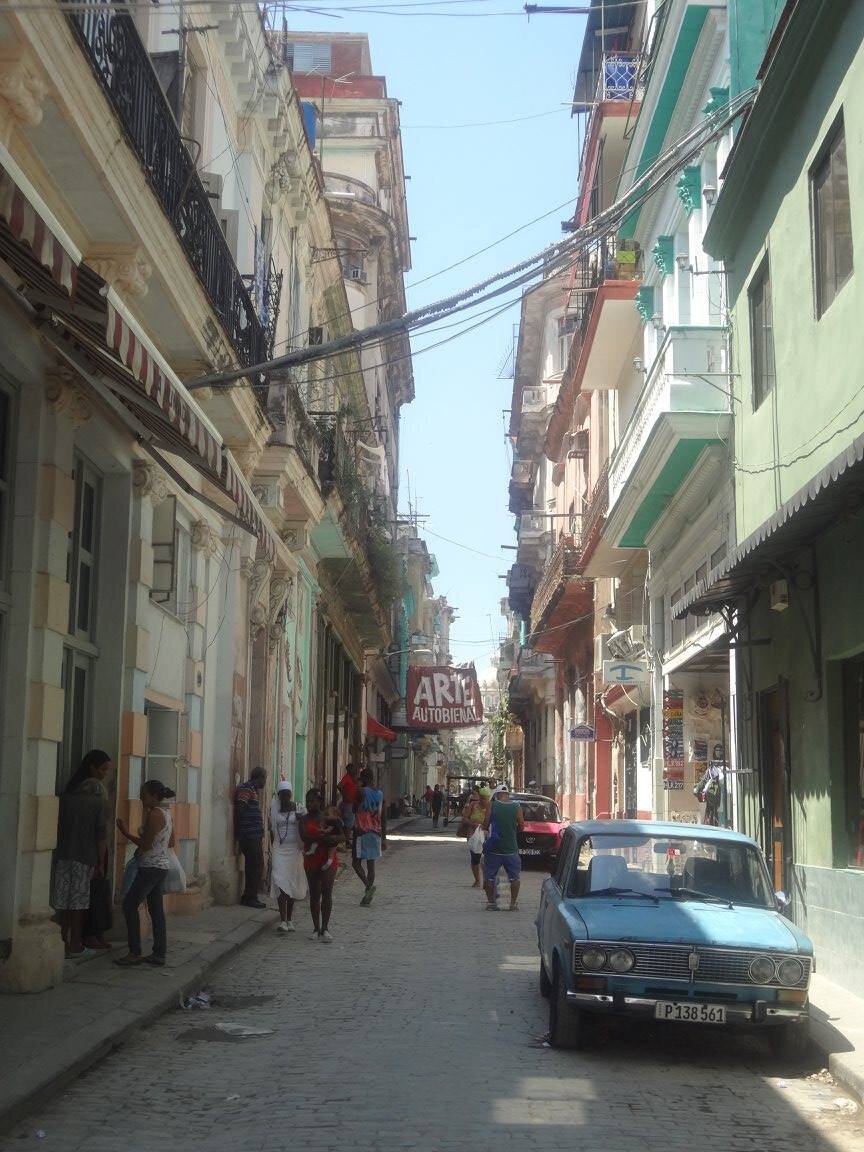

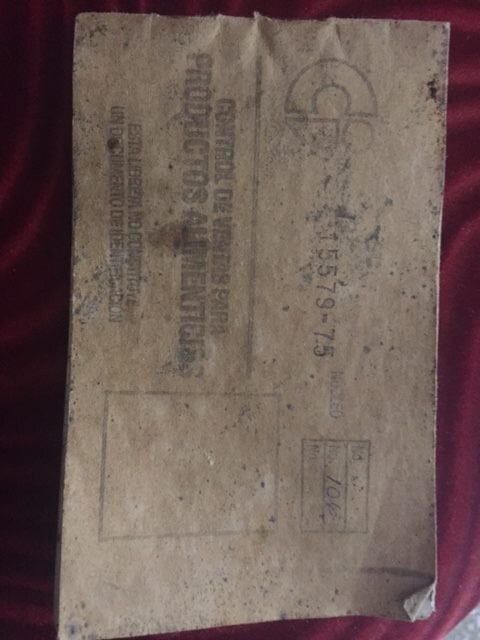

Read on for an exclusive excerpt from The Playwright’s House and for an inside look at photos which inspired the setting of the novel!

exclusive excerpt

(from Chapter 6)

Serguey remembered their home taking on a lively atmosphere following the last session with the child psychologist, when Felipe told his sons they had to turn the page toward a new life, cherishing the positive memories of their mother. During weekends, instead of making good on a weekday promise of a trip to the beach or the zoo, Felipe hosted dinner parties for his colleagues. People acted out scenes from their favorite plays and made fun of the obtuse administrators at the cultural centers where they worked. Once in a while someone would bring an acoustic guitar and play Nueva Trova songs. Felipe, however, rarely let his boys be a part of the celebrations, which made the few times he allowed them to remain particularly notable. Serguey recalled the laughter, the smoke snaking up from the ashtrays, he and his brother dancing for the crowd. These moments had washed over the otherwise dull, solitary lives they led under their father’s supervision.

As with Felipe’s current predicament, he hadn’t wanted to involve his sons in his personal affairs. During their childhood, he had given them fleeting kisses on the head, dismissive sighs at their misbehavior, quick waves of the hand in the mornings. He had, very seldom, shown them books, paintings, played them music—Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, Picasso’s Guernica, Bola de Nieve’s “Ay Mama Inés”—but he never related them to their actual lives, never linked what he shared to their daily struggle of growing up motherless. It was as if he believed that exposing young boys to art would be curative and edifying on its own. He never discussed his own work, either, not in the dim light of their bedroom or the ash-ridden air engulfing his writing desk, intimate places where their young minds would have been perceptive, prone to remember. He reserved himself—the vulnerable Felipe, the thoughtful and authoritative Felipe—for his circle of artist friends, for the stage he directed. Serguey and Victor had spent their lives watching like intrigued spectators, wondering about this figure that was their father.

This excerpt is from The Playwright's House by Dariel Suarez (Red Hen Press 2021). Reprinted with permission from the publisher.

Photo credit: Dariel Suarez

Interview

Author Dariel Suarez

Illianna Gonzalez-Soto (IGS): Dariel, do you mind telling me a little bit about your debut novel, The Playwright’s House (Red Hen Press, June 2021)? Who or what were your inspirations for this story which is fiction, but which may be partly based on your real life experiences in Cuba?

Dariel Suarez (DS): I wanted to explore the complicated intersection between arts and politics in Cuba through the lends of a fractured family. It also felt important to highlight the reality for political prisoners on the island, and the nuances of contemporary life there. Some of the places and people are inspired by my own experiences growing up in Havana, but the vast majority of the book came from research and imagination.

IGS: State surveillance, freedom of artistic expression, estrangement, love, differences between class and wealth. These are some common themes present within The Playwright’s House. Can you speak more to how the characters reflect these themes within the novel?

DS: Every character in the book is contending with both internal and external forces. A place like Cuba makes it very difficult to ignore the social, economic, and political reality of the country, as it constantly impacts most people. I also wanted to show the subtle differences in class and culture, to counteract the more stereotypical or monolithic thinking about the country for those who aren’t as familiar with it.

IGS: Jumping off the last question, it seems like love and estrangement are especially prevalent. The brothers, Serguey and Victor, begin the novel completely at odds. This is also true for their relationship with their father as well. Can you speak more about how the brother’s relationship with each other evolves throughout the novel? Why was their relationship as siblings central to pushing the plot forward?

DS: The relationship between Serguey and Victor was the main engine for the novel as I wrote it. They have so much to contend with in their past—resentment, violence, jealousy—while trying to help their father. I feel like through their shared journey, they give themselves a chance at reconciliation and redemption, even if they don’t always see eye to eye.

IGS: The father is especially engaging as a character, if not only for his part as a playwright. Serguey seems especially opposite to the dramaturgist because of his career as a lawyer. Why were you drawn to center this story on the art form of theater as opposed to a painter, or a poet, a novelist, or a musician such as yourself?

DS: Theater in a place like Cuba serves many functions: escapism, experimentation, cultural expression, and sometimes, subversion. It can be a way for artists to engage with some of their social and political frustrations they feel, but there’s always a risk when you do so there. For a renowned director to be arrested, it’s a very public event, harder for the government to hide. All of these things provide a strong platform on which to build a larger story and explore the different layers and staked of being an outspoken artist in Cuba.

IGS: There are also many supporting characters who aid the brothers in investigating the imprisonment of their playwright father. Ana (Serguey’s wife) and her family, the Catholic priest, Kiko (internet extraordinaire), a Santeria priestess, and Claudia (journalist and activist). What purpose do each of these roles play in portraying the realities of a Cuba that existed 20 years ago and which still may exist today?

DS: Having a broad cast of characters allowed me to delve into different areas of Cuban society and to present either opportunities or obstacles for Sergey, the protagonist. These characters gave the plot some energy and kept the story grounded in the inter-personal, despite the external forces at play. Moreover, I wanted to show some diversity in the Cuban experience, which often tends to be oversimplified or looked at through a singular lens.

IGS: What research went into creating your novel? Certainly this novel is based on a very key historical reality in Cuba, The Special Period, which existed until roughly twenty years ago. Along with the Castros, are there other specific figures which may have stood as inspirations for your work?

DS: I wasn’t focusing on any one person’s life, but a lot of what takes place in the novel was inspired by research. There are numerous reported accounts of government oppression and abuse, of artists being arrested or forced into exile, of the Church being involved in assisting political prisoners, of independent journalists using social media and blogs to bring attention to what’s happening in Cuba. I wanted the freedom to explore and take the story where it needed to go, so my approach was grounded in compiling lots of information and examples, then infusing what felt most useful and earned by the narrative and characters.

IGS: You immigrated with your family to the United States when you were fourteen. Can you talk about what being between worlds (Cuba and the United States) was like as the author of a story primarily set in Cuba? What political or cultural similarities/differences do you see reflected within your work?

DS: Questions of identity are inevitable when you migrate permanently, especially after having had an entire childhood and early adolescence in a different country. Cuba is my birthplace, my native culture. Writing about it is a way to not just feel closer to it, but to interrogate my relationship with and perception of it as someone who no longer lives there. It’s also an opportunity to give voice to certain people and issues that writers on the island wouldn’t be able to do for political reasons.

IGS: I’ve read your LitHub article. Can you speak to how being a non-native English speaker impacted your career as a writer, especially when writing The Playwright’s House? Do you have advice for native Spanish speakers hoping to publish in a predominately American / English language landscape?

DS: I don’t know if I’m in a position to give advice, since individual experiences tend to vary, especially with something as complex as language. I’ll say that, for me, becoming clear on my intended audience, how I define cultural authenticity in my work, and my use of language has been a long road. My recommendation would be to read as widely as possible, especially when it comes to contemporary international literature. That was life-changing for me, because it helped clarify my own artistic sensibility and approach, and resist some of the more harmful (e.g. culturally myopic) feedback I received in the U.S.

IGS: You're not only an insanely talented writer, but a musician as well. How do the two artforms inform each other? What advice would metalhead Dariel Suarez say to writer extraordinaire Dariel Suarez? Is there a song, album, or playlist that is quintessentially The Playwright’s House?

Metalhead Dariel Suarez

DS: Haha! Metalhead Dariel would definitely not call writer Dariel “extraordinaire.” Music taught me to be patient and to treat art as a craft. If you don’t put in the time with an instrument, it will show. The only way to get better is through dedicated—and sometimes grueling—practice. Music also taught me to collaborate, to be open-minded, to explore in search of something better and not settle for the first idea (a nice melody or riff is something to build on, not the final product). Teaching myself to play guitar was literally painful. My fingers bled, my hand and arm muscles hurt. All those metaphors people love to throw around about how hard writing can be feel quite real with music. So by the time I decided to become a writer, I wasn’t looking for shortcuts or going after some romanticized version of the art-form. I was ready to put in the work.

IGS: You serve as the Educational Director with GrubStreet. What final advice or tips do you have for aspiring Latinx writers with a hope to publish their works?

DS: Seek out your community. You don’t have to go at it alone. Read as widely as possible, and by that I mean in terms of country, identity, lived experience, style, time period. Consume art with a critical eye and put into your tool box that which speaks to your own sensibility and interests the most. Don’t let others define you as a writer or tell you what you should ultimately write, or for whom. Go after the questions, people, and places you’re intrigued about. Trust that all you need is dedication and persistence, especially in the face of obstacles or failure. Those who push forward are the ones who break through.

To stay updated with Dariel Suarez, follow him here:

Twitter: https://twitter.com/DarielSuarez1

Website: https://darielsuarez.com/

Illianna Gonzalez-Soto graduated from Earlham College in 2020, where she served as an editor for The Crucible. She obtained a BA in English and a minor in creative writing. She currently lives in San Diego, CA where she serves as a Media & Marketing intern at Red Hen Press and Latinx in Publishing. You can follow her on Twitter (@Annalilli15) and Instagram (@librosconillianna).