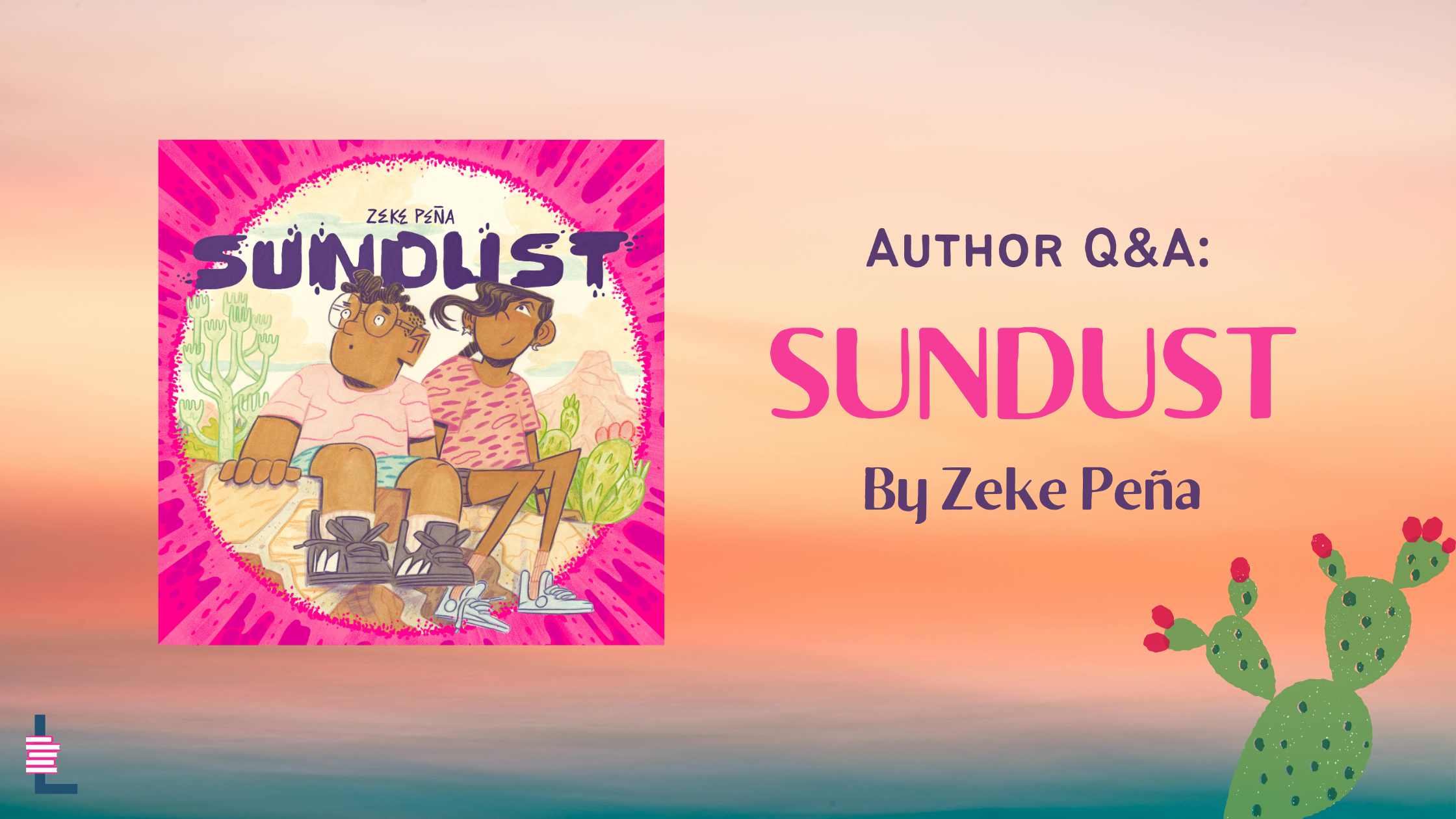

Zeke Peña’s author-illustrator debut, Sundust, begins with the image of two siblings jumping over a rock wall to the other side.

He writes: “Where the rock wall ends, the desert beyond begins.”

Their adventure in the desert begins, over a bulldozer and an abandoned pickup truck, over ocotillos with their tall, spiny stems. The siblings climb and jump in el desierto, following their curiosities. They notice an old nopal tree and liken it to their mother, who they say is tough and prickly, too. They marvel at an ancient looming rock. They “feel the Sun’s tough love on our skin.”

In Sundust, Peña, the award-winning illustrator of Isabel Quintero’s My Papi Has a Motorcycle tells an immersive and fantastical tale of the connection between people and place. The inspiration behind the book is Peña’s own love for the desert that he grew up around. “I think it’s such a unique region, and it’s an area that requires resilience to live in,” he told Latinx in Publishing. “I wanted to honor that.”

Peña spoke with us about creating his highly anticipated author-illustrator debut, depicting the desert as its own character, and much more. Out now, Sundust and the Spanish edition, Polvo Solar, were published simultaneously.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Amaris Castillo: Congratulations on Sundust. I understand you grew up around a desert. What inspired this book?

Zeke Peña (ZP): The main thing is love for the desert, for the place that I came from, and for my people that come from there and people who live in desert areas. I think it’s such a unique region, and it’s an area that requires resilience to live in. I wanted to honor that.

On a personal level, being able to play in the desert when we were kids was a really special time. As I’ve gotten older, I realize how special that time was to learn things from being outside, and walking and running around. Even if you’re not from the desert and you’re from a different area and climate, there’s something there about how the places we come from shape us, and how they provide us with a sense of belonging that I think young people now are sometimes a little distant from.

I’ll speak specifically to my community. As El Paso gets more developed and as things continue with what’s going on in the country, a lot of the focus is on the border. Everything is centered around that, so all of the attention is centered around that — not only for people who are outside of our community, but for our young people inside our community. I’ve gone into schools and I’ve talked with young people about our river. Their only understanding of the river is of it being a border. What does that do to our person? And what does that do to our community and our relationship with the place that we’re from? Unfortunately, it sometimes distances us. While I’m proud of being from the border, I also think it’s really important to remind ourselves that the place that we’re in existed before there was a border there. And so how does that place — with the animal and plant friends that live there as well — shape us?

AC: As a child growing up in El Paso who played in the desert, how did you view the desert as a child?

ZP: I haven’t had the opportunity to elaborate on this yet since making this book, so I appreciate the question. As most young people who have the opportunity and the privilege of living in one place, I don’t think that I had the objectivity to know anything else. What I knew was dirt and rocks, and it being very hot — and running around in a place where there’s a lot of sky. That was something that I was really aware of: the sky and how big the sky is. The sky, for me, was really a place for imagination. Early drafts of the story focused on this idea of being bored of the place that I am from. It can be a really boring place. So that idea of the sky being a place where you’re encouraged to imagine, I think, was special.

A moment in the book that comes later is around sunset… it’s a quiet time. As people living anywhere, we acknowledge sunset in a special way that makes us inherently feel more quiet and calm. That was something that always stayed with me and resonated throughout my life, was spending time around sunset to be quiet and to acknowledge the beauty that is in the sky.

“Even if you’re not from the desert and you’re from a different area and climate, there’s something there about how the places we come from shape us, and how they provide us with a sense of belonging that I think young people now are sometimes a little distant from. ”

AC: You have illustrated books by notable authors like Isabel Quintero and Jason Reynolds. But this is your debut as the creator of both the text and the illustrations. How was it to be in charge of both, and in ushering this book to life?

ZP: It was really difficult for me. It took me a long time to adjust my frame of thinking. It was like double pressure: I was creating my second picture book, and there was the pressure of following up something that was received really well by the community and by publishing in general. It was also the first time that it would be my voice in the book. Having worked with other creatives, I have the skill of being able to prioritize someone else’s voice. It’s a good trait to have as an illustrator. But it took me a little bit to make that adjustment of centering my own voice. Personally, I had a hard time with getting to that place of being confident with what I was putting on the page.

I’ve been writing comics and writing poetry for a really long time, but it wasn’t necessarily something that I was focused on. It was also work that I would often self-publish… So it was nice to revisit that thinking and find the workflow. That was the most difficult thing; I was so used to having Isabel in the room because we had worked on a couple of things before. It’s very collaborative and conversational, and we’re bouncing ideas off of each other… After getting to a place where I felt confident, after rewriting so many different drafts and redrawing things, I was able to get good with what’s on the page. I feel like I was able to work through that so that I can continue doing it and make more books.

AC: The desert, of course, is its own character in Sundust. What considerations did you make when figuring out how to depict it on the page? The desert is such a big character. It’s like a third character.

ZP: That was the tough part. There are so many different characteristics to the desert. Obviously, not every desert looks the same. I’m from what’s referred to as the Chihuahuan Desert, and there are specific plants that grow there. Because this book is fantastic, I stretched it; some of the plants that are in the book don’t look like where we’re from. It’s an exaggerated kind of reality in the book. Some of those plants are really unique to the area. For example, creosote, also referred to as “gobernadora,” is used as a sacred plant. It’s utilized in different ways, but it’s also the plant that gives the rain a very special smell. If you have people from El Paso, they’ll know the smell.

The considerations I made were including things that would have that special memory or that special connection to the place. Or things that are not alive, like the rock wall; we have really unique walls that look a very particular way in that area. And so how do I summon something that’s going to resonate with the people who are also where I’m from? That was the main consideration.

AC: What do you hope readers take away from Sundust?

ZP: To have the curiosity to get outside of where you are on a daily basis — if you’re inside and have space where you can be outside, because some folks live in areas that are mostly city or they don’t have access to outdoor spaces. Try to slow down a little bit, go for walks and pay attention to the things that are around us. We all have access to the sun. To pay attention to where the sun comes up and where the sun goes down. But I think just wild imagination, to dream wildly and to think of fantastic things.

Zeke Peña is a Xicano storyteller and professional doodler from Sun City, TX. Sundust, his author-illustrator debut, hits shelves in Summer 2025. He recently illustrated the New York Times bestselling Miles Morales Suspended: A Spider-Man Novel. Zeke was awarded the Ezra Jack Keats and the Pura Belpré Illustration Honor for My Papi Has a Motorcycle. He also received the Boston Globe–Horn Book Award for his illustrations in Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide. He is currently drawing more books in his tiny studio that used to be a mop closet in NW Arkansas.

Amaris Castillo is an award-winning journalist and writer. Her debut book, Bodega Stories, will be published in September 2026 from the University Press of Florida.