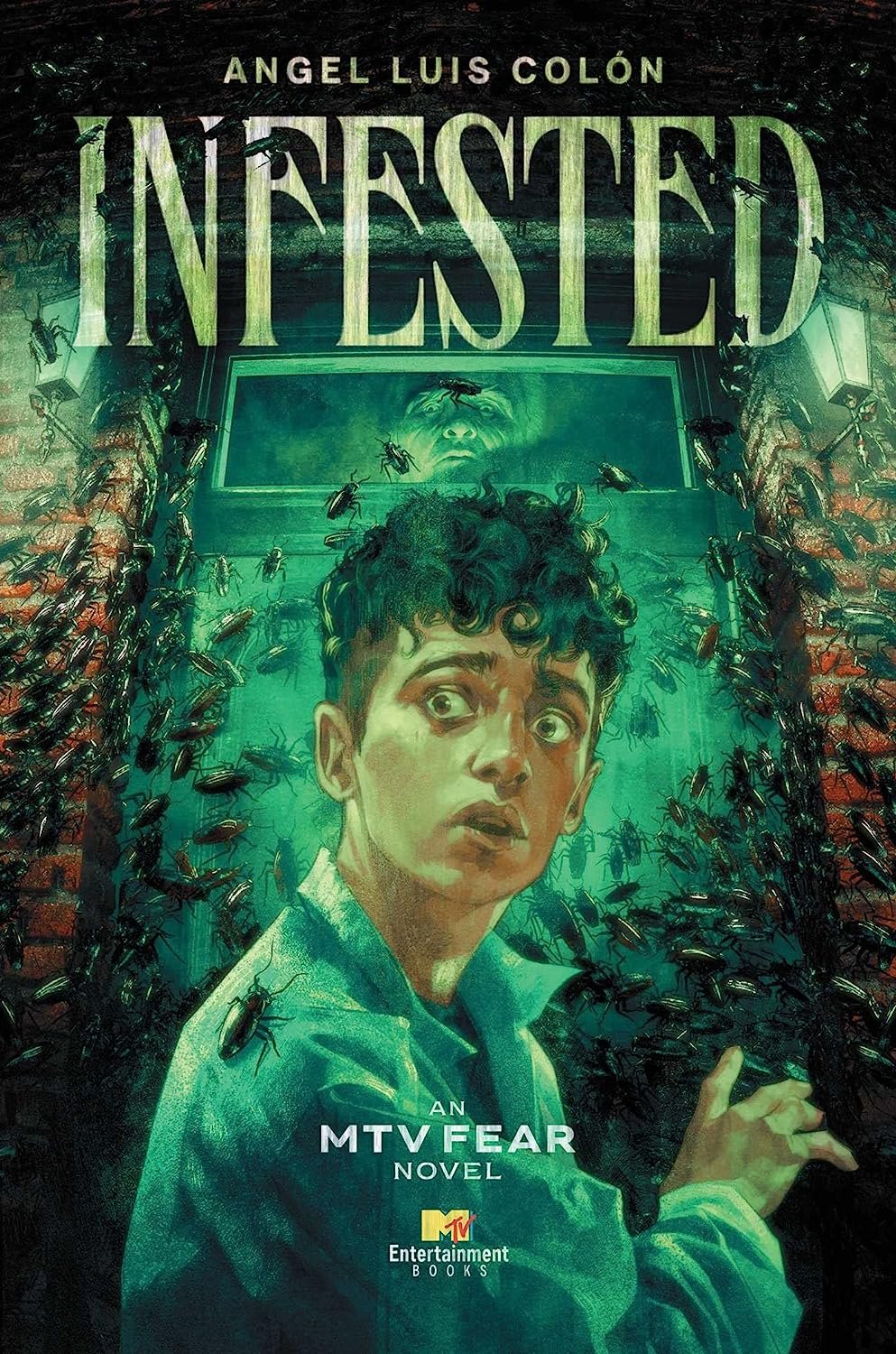

Amaris Castillo (AC): Congratulations on Infested! This is your YA debut novel. What inspired you to tell this story?

Angel Luis Colón (ALC): Initially I had been thinking about YA for a little while. I was coming from the adult crime fiction scene, and I wasn’t getting a lot of fulfillment out of it. I was very hesitant to write about my experience as a Puerto Rican from New York in that space, because of a lot of the negative stigmas that are perpetuated about Puerto Ricans—especially in crime fiction. You see TV, you know, all those things.

So I thought about: How do I write about these things I want to write about, in a different space that maybe is a little safer—that’ll let me explore things? My agent came to me with the news that MTV Books was coming back, and they were looking for ideas. We were having beers, and something just kind of struck me as an idea I wanted to look into. I pitched it to him, and then we pitched it to MTV, and it kind of blew up from there.

At first, it was like an interesting idea, right? But I think YA lets you explore things a little more allegorically. You can kind of go a little crazier. When that clicked, I was like, well, wait a second. There’s a lot of things we can talk about the Puerto Rican experience, at least in New York, and also bridge my upbringing in with it. As most Nuyoricans will know, you’re blanquito growing up. There’s a level of privilege that comes with that. There’s a level of issues that come with it, as well. But I decided I wanted to write a story about that point a white Latino has where you got to decide: Are you going to embrace the privilege? Or are you going to think about your place within your culture, and what role you can play to help it?

AC: Your main character, Manny, starts off feeling like he hates his mother and stepfather for moving their family from Texas to the Bronx, in the summer before his senior year. At first I chalked this up to teen angst, but there are other dynamics at play when it comes to his relationship with his parents. What message were you hoping to send by highlighting this tension between a child and his parents?

ALC: I found an opportunity with that because I thought about my own tensions with my family coming up. It goes back to what it is to be Nuyorican, Puerto Rican. On paper, however you would describe it, I guess I’m third-generation American. Being Puerto Rican makes it funny to describe it like that, right? Because we were made American on paper, and whatever that means, too, but I digress.

But there are very stark differences between generations. And I realized a lot of my own angst came from how much more Americanized I was from my mother, versus how much more Americanized she was from her mother. You think about all these milestones we look at culturally. And, like you said, a senior in high school is so important, right? But really, is it? It’s important because we’ve been told it’s important. And there are reasons for it being important, like college and all that. But to a teen’s mind, they look at it as important because they’ve been told all of their lives. When I thought about all that (older) generation, my mom never cared. That wasn’t something that she had to care about. For her and her generation, senior (year) in high school was the end. There was no college. There was no thought beyond that. You went straight to work. So I wanted to play around with that.

I thought hard about how I had the privilege of being like, ‘Well, this is such a pivotal time in my life. I’m going to have college.’ And the people older than me are like, ‘What are you talking about? You gotta live.’ It helped me with that balance between how his mother and stepfather were just kind of like ‘We’re moving. This is an opportunity. Why are you so upset?’ They don’t grasp it, because, to them, they’re doing the right thing based on where they’re coming. In their minds, providing for family and working are the two most important things. But to Manny, he has had the privilege to be able to have a little more long-term thinking. So for him, he’s like, ‘Well, I hadn’t started yet. What are you talking about?’

AC: Your book definitely has the ick factor by way of body horror. There are moments that had me looking around to make sure there are no roaches near me. What was it like for you to bring this subgenre of horror to a younger audience?

ALC: That was really important to me. I actually thought about that a lot, and I wrote about it recently for CrimeReads. My first horror movie was the 80s remake of The Thing. I was only five years old, and my uncles thought it would be hysterical to show it to us—me and my three cousins. I ran out of the room. I was mortified and just completely traumatized.

I was not a fan of horror until maybe five or six years later, and we saw this movie called The Gate. It was awful, but it made me realize that you can find different types of horror. And then I would go back to the crazier stuff but I realized, when you’re young, that stuff is very scary. I look at my own kids and see how they react to certain things, and I’m like, ‘Oh, OK.’

I wanted to think about it that way—what can I write for somebody who is kind of like a gateway? Isn’t too extreme, but isn’t too nice either. Something that one reader out there will be like, ‘I want to check out some other stuff.’ I got a kick out of that.

AC: When Manny meets Mr. Mueller, the building’s exterminator seems friendly. Manny and his new friend, Sasha, later discovers that Mr. Mueller is a specter who espouses certain beliefs about their Bronx neighborhood. Can you share how you landed on this paranormal aspect while writing the novel?

ALC: Initially I wasn’t going to, but then I felt like that was a little too real. I grew up in the Bronx. I was actually born in Texas—where I pulled the Texas thing for Manny from—but I was only there for a couple years. My parents divorced, and I kind of grew up solo and I was raised by my grandparents and different men throughout my life. A lot of them served as mentors, but also were very entrenched in their way of thinking. So I pulled a lot of that into Mr. Mueller—it’s having this person that you can bond with that is problematic. That was very common when I was growing up in the Bronx, because you have this very weird melting pot of folks. And a lot of the older folks would have incredibly antiquated views, and they were very stuck in their ways.

There was one guy I grew up with, the father of my mother’s best friend. He was an incredibly racist old man. It was a very complicated relationship with him, because he had a charm about him. You can get along with him and he would make you laugh, but then he would say something that was just insane. It was easy for him. It wasn't even awkward. So I wanted to channel into how that hate becomes like an infestation. It’s something that you can’t just scrub out.

At first, we were gonna keep Mueller pretty grounded, but I felt like that was just way too real. And I really wanted to go into the paranormal things. So we decided: How do you create a character that’s allegorical to that, and is kind of like this physical manifestation of that grime that grows on people’s souls? It clicked: We’ll make him make him a ghost, and we can loop in Bronx history into that.

AC: In Infested there’s an added storyline about gentrification, class, and this question of who belongs where. Can you talk about your decision to anchor your book in these themes?

ALC: If you’re not from the Bronx, there’s always a stigma around the Bronx. Growing up, when people would meet me, they’d be like ‘You’re tough. You’ve seen people explode or die.’ Lots of nonsense. And that all stems out of the 70s, when the Bronx was on fire and you had the influx of lots of Latino and Black people that were leaving the island when Harlem was being gentrified, actually. I grew up with that stigma, and at the tail end of the worst times that the Bronx had.

Yeah, I saw some things, but there’s still humanity to the neighborhood. There’s still a very proud culture to it. I think the Bronx had this distinction of having that stigma working for them, in a way that gentrifiers avoided the Bronx. So when Brooklyn was really getting built up, people just ignored the Bronx. Then that changed, and when I’d visit I started seeing new buildings, things were shifting, and rents were going up. And for a while, I kind of deluded myself into thinking ‘Well, we’ll never let this happen. We’re too in here. We’re too strong.’ You can tell yourself that, but money at the end of the day is always going to beat you if you don’t have it to fight back. And I began to see real changes in the neighborhoods I grew up around.

At first you’re like, ‘A new building can’t be a bad thing. New businesses can’t be a bad thing, right?’ But you begin to realize these businesses aren’t meant for the people there. And that’s where the real problem starts. I thought a lot about that, and realizing that the Bronx is changing now. And it’s a bummer to me. Growing up in the neighborhood I grew up in, you don’t want to see what made that neighborhood so special to you change. I always felt like I was a very fortunate person growing up in the Bronx. I was able to be around Latino people, I was able to be around Black folk, Asian folk. It was really cool. And it’s such a bummer to think about that going away. I wanted to really get into that, and I thought it would be an interesting thing to have the main character of the story be part of the problem. Maybe not by choice, but he’s there and he’s living in this building.

AC: What are you hoping young readers take away from Infested?

ALC: When I really got into things, I realized I was putting a book together that I wanted to read at that age. I wanted to write a book for a blanquito who is out there, maybe in the same situation I was at that age and other white Latinos are—where you’re at that impasse. You can embrace your privilege and be the token of a white group, and continue on some weird path. Or you can sit back and begin to think about your culture and what you can do for it, and how you can be a better ally to the Black folks in the Latine culture. They’re consistently written-off people who are part of you as well. And that first step to decolonization. I really was invested in that.

I didn’t want to be another Latin writer who was just playing around in the marginalized space to make white people feel comfortable. That was a big concern of mine, especially thinking about my own privileges. Because, very often, white Latine writers, white Latine performers, and other creators are used, to be tokens—to make that check, where it’s like, ‘We got the representation.’ So I very much wanted to call that out. And I wanted the book to be about colorism and gentrification because of that.

I wanted to push back against those two pieces. The two pieces that I always see are either using us for our pain, or using us as a filler to provide safe stories. It’s tough to navigate, and you never know if you get it quite right. That’s the hard part about it, because it’s complex. But my hope is that readers take that, and that readers like that. I want everyone to be able to see maybe a little of themselves in the story through Sasha, or through someone else like Manny. And see the things that they grew up around, at least represented somehow.