When 12-year-old Maricela Yanet Feijoo isn’t at school or with her best friends, Keisha and Juan Carlos, she can sometimes be found wincing at what she calls her family’s “Peak Cubanity.” She also worries that her next-door neighbor and classmate—who she calls “Mocosa” Mykenzye—will judge.

“Peak Cubanity” is what Mari calls her family’s behavior when she feels they’re being over-the-top. And she’s got many examples from which to draw from on New Year’s Eve because that’s when she says they reach Peak Cubanity. It’s the day Abuelita lugs a suitcase around the block because she wants to travel the upcoming year. And Mami sweeps and mops the whole house, leaving a bucket of dirty water by the front door, so that she can throw it out at midnight.

“At least we won’t be eating twelve grapes at midnight as fast as we can,” Mari narrates. “When I almost choked last year, Papi had to do the Heimlich maneuver on me and everything. I shot a green grape straight out of my throat and into the eye of my sister, Liset. Maybe something that’s supposed to bring you good luck shouldn’t also try to kill you. Just a thought.”

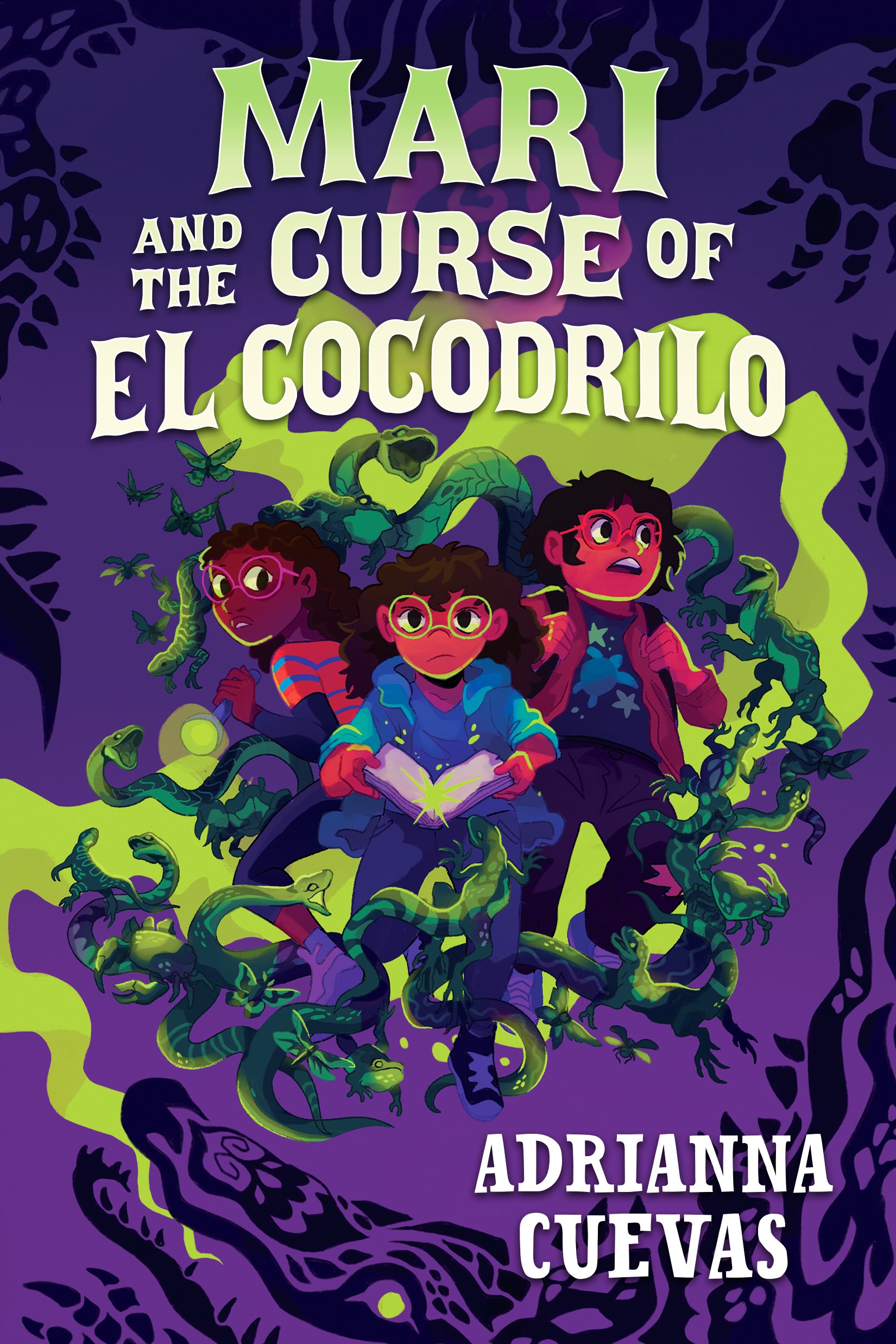

“Cuevas brings readers another memorable story that will both make you chuckle and feel deeply for a young girl finding her place on her family tree.”

Which is why at the start of Adrianna Cuevas’ new middle grade novel, Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo, the titular character declines to participate in her family’s biggest New Year’s Eve traditions: burning an effigy to rid themselves of the past year’s bad luck. But after Mari fails to throw hers into the fire, strange things begin happening. Bad luck falls upon her, then spreads to her friend, Keisha.

Out now from HarperCollins, Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo is a heartfelt and humorous story about one girl’s journey toward self-acceptance and learning how important it is to know your family’s history. Spooky vibes and silliness also permeate the book, as readers witness all kinds of things happening to Mari. Among them are uncooperative pencils during a quiz, a possessed violin and, in Keisha’s case, shoes that glue to the mat when she’s at fencing practice.

Once Mari discovers she has a unique ability to call upon her Cuban ancestors, she and her friends embark on a quest to work with the ghosts to try to defeat El Cocodrilo. Can they do it?

In Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo Cuevas brings readers another memorable story that will both make you chuckle and feel deeply for a young girl finding her place on her family tree. The Pura Belpré Honor-winning author spoke with Latinx in Publishing about crafting Mari’s story, preserving your family’s history, and more.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Amaris Castillo (AC): Congratulations on Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo! What inspired this story?

Adrianna Cuevas (AC): This story really came from a couple of avenues. First, I’m a horror fan. I’ve always loved horror. My dad took me to see Alien 3 when I was a kid in the theater, probably way younger than a child should have been seeing Alien 3 in the theater. That is a core memory for me. Part of it was this is my fourth published book now, and I’ve been writing mostly adventure. I was a little bit spookier with The Ghosts of Rancho Espanto, but I really wanted to dip my toe more into spookier stories for middle grade kids.

The emotional inspiration really comes from my own experiences, and different students that I’ve interacted with; those second and third generation kids who are trying to figure out how their parents’ culture and their grandparents’ culture still fits into their lives. Because I think sometimes you can feel a little bit more disconnected from it.

For me, growing up I didn’t hear about a lot of the experiences of my family when they were in Cuba. They didn’t talk about them. One of the reasons I wrote Cuba in My Pocket was because I wanted to hear those stories. A lot of times there’s kind of a disconnect, where you don’t have all the family history that a lot of other families do. My husband’s family is from rural Oklahoma and when his grandfather passed away, they had this shed full of all this stuff from generations and generations past that was connected to their family history. Everything had a story. And I thought, I don’t have anything like that. I have things from my dad, but they’re all from things once he moved to the U.S. I have one small jewelry box that my grandmother actually wrote on the inside, “I brought this from Cuba.” That is literally the only thing.

So that’s a long-winded answer to say I was drawing from my own experience of kids that feel like they’re wanting that connection, perhaps—or maybe they don’t—with their family’s culture. But they’re not quite sure how that works. Then, of course, I wanted to throw in some horror just to make it fun—because I can never help that.

AC: Your main character, Maricela—or Mari—cringes at how extra her Cuban family can be. She even has a term for it: Peak Cubanity. It reminded me of how some first generation Americans struggle at times to straddle two cultures—that of the United States and of the country their parents hail from. What was it like crafting this character who, from the first page, seems to shun her family’s culture at first?

AC: A lot of it was not entirely based on my own experiences, but drawn from them. I grew up in Miami, Florida. Growing up Cuban in Miami, Florida, is a super privileged thing to do in all honesty, because your culture is everywhere. Our music is on the radio. You have your choice of Cuban restaurants to visit. You would go out and do all your errands for the day, and never have to speak English once.

I did not feel that sense of ‘other’ until I went to college in Missouri, because that was my first time being away from an area where, in all honesty, my culture was the majority. And so I got that sense that Mari does, of ‘Well, who am I and how do I fit in? And everyone here assumes that I’m Mexican because I speak Spanish.’ That happened to me a ton. It especially happens to me here in Texas. And so I wanted to honor those kids who feel the same way. I mean, Mari loves her family. But what child of any cultural background is not embarrassed by their family ever so often?

I wanted Mari to experience the joy that you can get from learning your family’s history, but at the same time understanding maybe why you didn’t know all about it to begin with. Because a lot of it can be painful. That happened when I was researching Cuba in My Pocket. I’m asking my dad and my cousins, as well, of their experiences in Cuba and coming over to the U.S. And not all the stories are great. You can see why maybe kids don’t hear everything, and adults are reluctant to talk about it. A lot of it was drawn from my personal experiences. But if you’ve ever met Cubans, the “Peak Cubanity” fits because we are not a subtle people. And so I had a lot of fun just writing the joy and the extra that Mari’s family is.

AC: Your book is so lively with all the bad luck shenanigans that happen to Mari and, later, her friend, Kiesha. How did you come up with all the bad luck instances that happen? That was so fun to read.

AC: I will say that coming up with nonsense or just off-the-wall things is not hard for me when I am living with a now 16-year-old. Neither he—as my son—nor I have any filters. We tend to bounce really silly ideas off of each other all the time. I think as a creative person, it is really important to have someone like that in your life who doesn’t edit your creativity. They encourage you.

In all honesty, I’ve gotten into the habit where, if an idea pops into my head—even if it’s really off-the-wall—I’m not self-editing right away. I think that happens to a lot of authors, where you come up with an idea and the very next spot is, ‘Oh, no, that’s dumb. Nobody’s gonna want to read that.’ Because I have people in my life—my husband, my son—who are always encouraging my ideas and helping me brainstorm even the most nonsensical thing, I really value that as somebody in a creative profession.

It’s not hard to think of off-the-wall things when you’re just kind of letting your brain go. I always joke that as a Cuban, it’s very easy to write horror. It’s very easy to write a character that’s been cursed with bad luck. By and large, because of our political history, Cubans tend to be pessimists in all honesty. They’re gonna look at a situation and pretty much assume the worst is going to happen. That’s the whole function of horror, is asking, ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ And so I feel like I was at a cultural advantage, thinking: ‘Well, what’s the worst that can happen to Mari in this situation?’

AC: You’re like, ‘I got this. I’m Cuban.’

AC: Exactly. Like, I was already being a pessimist about this situation. I knew what was going to happen.

AC: There’s another storyline here about the importance of documenting the stories and memories of family members who are deceased. What message were you hoping to send by highlighting this?

AC: I realize that for each of my books, it’s really my way of hanging on to something that I think is important, and that I think needs to be remembered. . . In Mari’s story, it’s my way of showing that, ‘This is why that’s important. We’re not going to have all these people around forever.’ You know, Mari only gets a lot of the stories from ghosts. We can’t let that be our option, where we’ve waited too long to preserve our family’s history.

One of the things that I am passionate about is the ability to tell our own stories, before someone else tells them for us. We need to remember and commemorate what’s happened to us before somebody else decides to tell our own history. And so I think that’s something I’m pretty passionate about because it’s now come up in pretty much every single manuscript I’ve written. I always have the adventure plot, the horror, the silliness, whatever—but the emotional core of all my stories is always going to come from something that I feel is important to remember. I think that’s why I addressed the story the way I did.

AC: What are you hoping readers take away from Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo?

AC: I never go into writing any of my books with a lesson in mind. Because, for me, I want young readers to dive into one of my books. I want them to lose track of time. I want them to forget where they are, and I want them to just enjoy a story. That’s my primary goal with every single one of my books.

With Mari though, it would make me pretty happy if it made a young reader curious about their own family’s histories, start asking their elders some questions, or asking to be told stories. But by and large, I’m always just wanting my readers to have fun with my books.

Adrianna Cuevas is the author of the Pura Belpre honor book The Total Eclipse of Nestor Lopez, Cuba in My Pocket, The Ghosts of Rancho Espanto, Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo, and Monster High: A Fright to Remember. She is a first-generation Cuban-American originally from Miami, Florida. A former Spanish and ESOL teacher, Adrianna currently resides outside of Austin, Texas with her husband and son. When not working with TOEFL students, wrangling multiple pets including an axolotl, and practicing fencing with her son, she is writing her next middle grade novel.

Amaris Castillo is an award-winning journalist, writer, and the creator of Bodega Stories, a series featuring real stories from the corner store. Her writing has appeared in La Galería Magazine, Aster(ix) Journal, Spanglish Voces, PALABRITAS, Dominican Moms Be Like… (part of the Dominican Writers Association’s #DWACuenticos chapbook series), and most recently Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology and Sana, Sana: Latinx Pain and Radical Visions for Healing and Justice. Her short story, “El Don,” was a prize finalist for the 2022 Elizabeth Nunez Caribbean-American Writers’ Prize by the Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival. She is a proud member of Latinx in Publishing’s Writers Mentorship Class of 2023 and lives in Florida with her family and dog, Brooklyn.