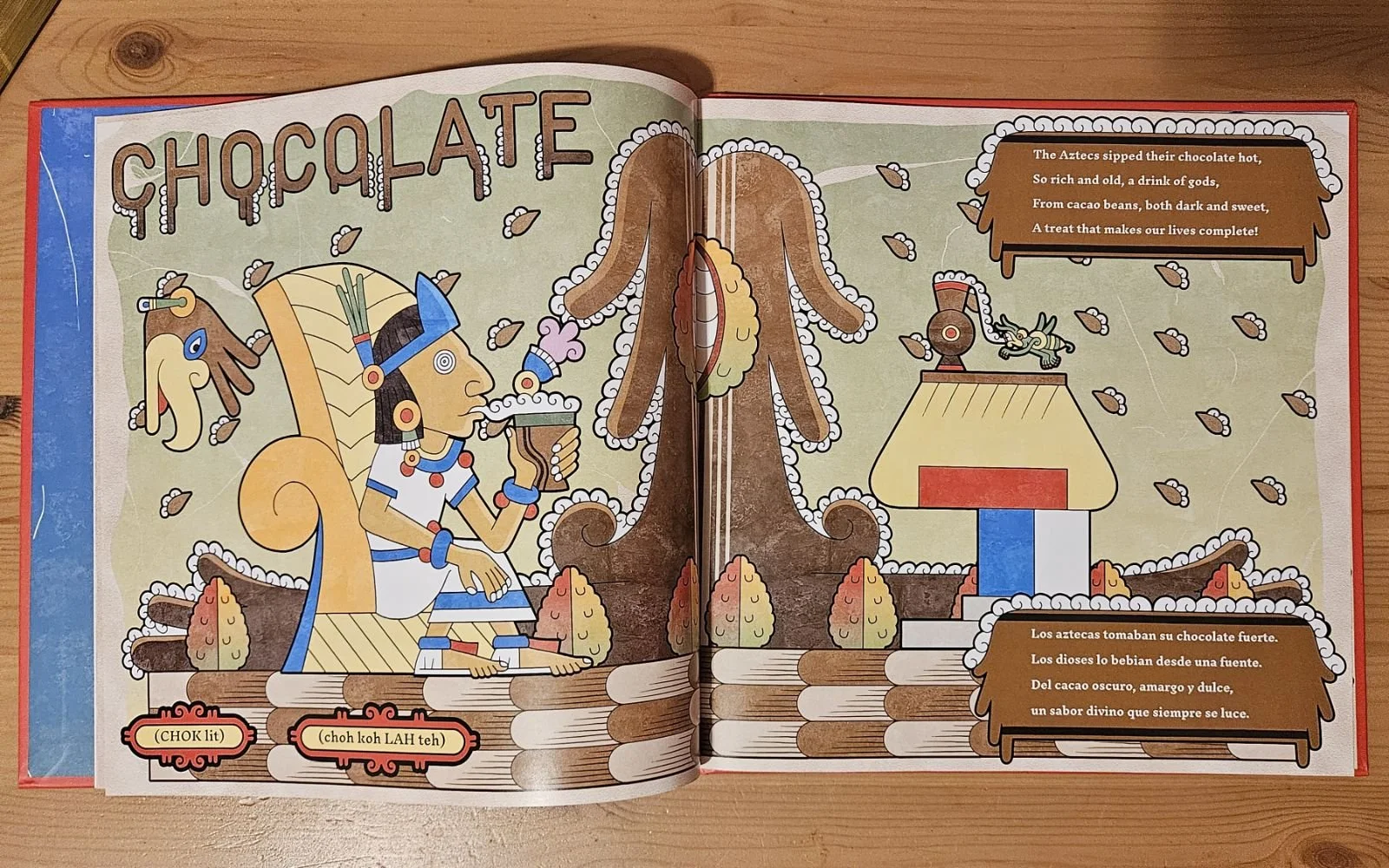

Author and Illustrator Emmanuel Valtierra’s picture book, A-Ztec: A Bilingual Alphabet Book (Levine Querido, 2025), delivers a beautifully artistic introduction (with pronunciation guides) to the A-Ztec: A Bilingual Alphabet Book. Written and drawn in dual form (English and Spanish), readers are introduced to Aztec words in an artform inspired by Aztec codex-style imagery. Alongside the already cool concept, audiences will learn more about Aztec and Mexican culture.

YVONNE TAPIA: Hey Emmanuel! Thank you for being here, we’re so excited to learn more about your work and journey as an author. How did the Aztec culture become a part of your everyday?

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Hi Yvonne! Thank you for meeting with me. My parents are from Mexico, and when I was in elementary school, I came across an Aztec codex. I wasn’t really excited about it at first because, as a kid, you don’t always pay attention to details. Kids usually care about topics like Bugs Bunny. (both laugh) I was a huge fan of Bugs Bunny and Dragon Ball Z [back in the day]. However, the Aztec codex stayed in the back of my mind, it was pretty cool to me and at that age you’re like a sponge and everything tends to [stay with you].

YVONNE TAPIA: Definitely, I loved watching those shows too and codices are cool tools – A codex is a manuscript book, often written in papyrus or parchment – serving as the historical ancestor of the modern book format. To our readers, if you haven’t learned about codices yet, we invite you to find out more information about them!

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Haha, exactly. As I grew older, when I was around 15 or 16, one of my good friends came up to me with this book, it was called “Aztec”, an old novel by Gary Jennings – great novel – and that is when I actually fell in love with the Aztec culture. It’s still my favorite book of all time to this day.

When I reached my early 20s, I started wanting to do something related to the Aztecs. So I started drawing, mixing the Aztec concepts with pop culture. I started a Facebook page and as I continued to post my artwork, eventually I had about 7,000 new followers! I had drawn a Dragonball Z image, gymnastics style. About a year and a half later, I self-published a book focused on what would’ve happened had The Aztecs won the war against the Spaniards – alternative history. I illustrated that book and a friend of mine wrote it, and we won the Sidewise Award – which is an award for alternative history books.

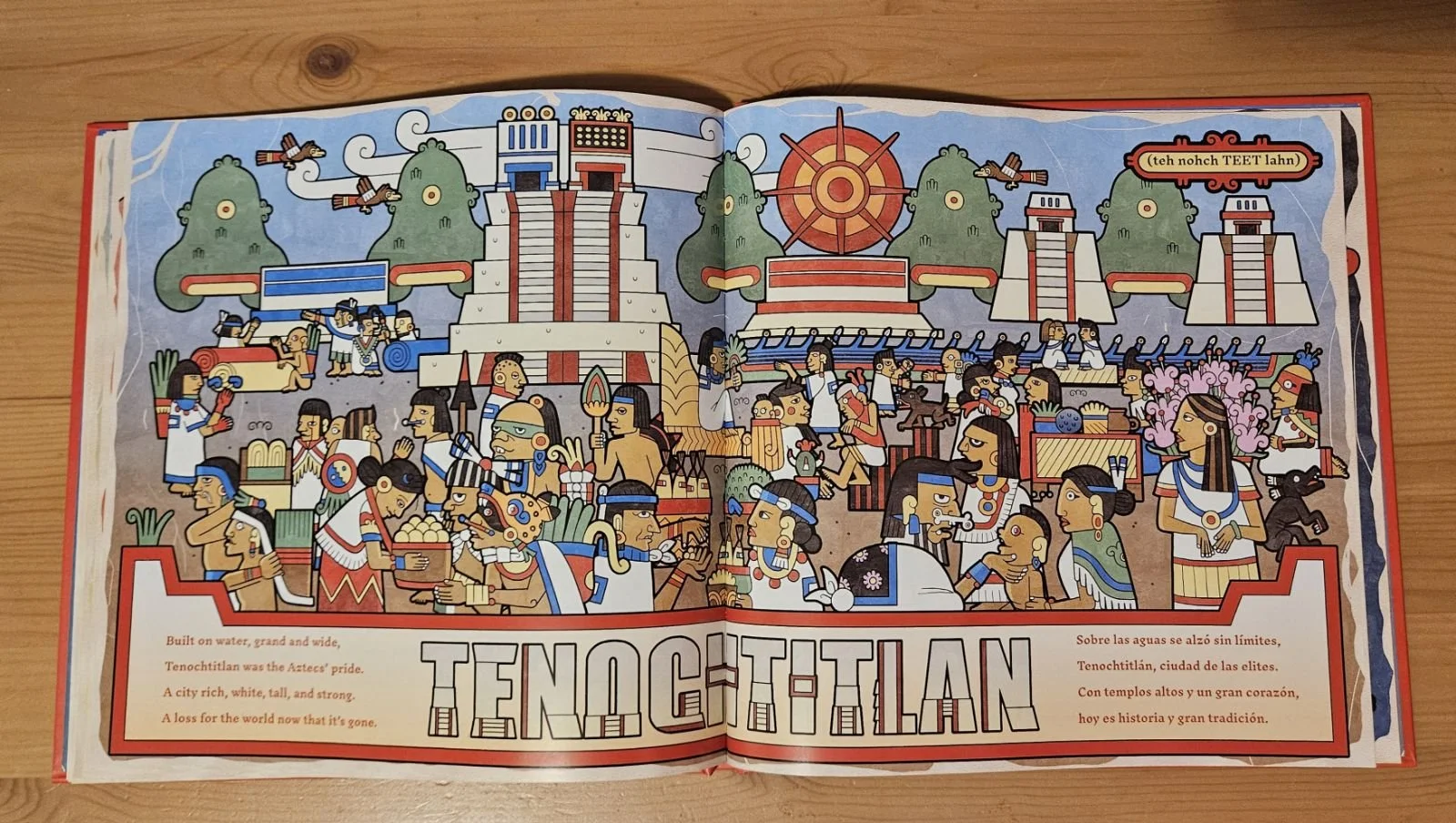

YVONNE TAPIA: Congratulations! You were just beginning your journey through these historical civilizations. Mexico City was known as Tenochtitlan back then.

Photo credit: Yvonne Tapia

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Yep, many thanks! A few years later I met with Vivian Mansour, the writer of Codice Peregrino (Pilgrim Codex in English). We met and she gave me the concept of a “peregrino”, and then it started evolving as my editor and I discussed an alphabet book introducing the Aztec language, Nahuatl, through Aztec codices. I believe it’s very important to continue showcasing past civilizations [for a better tomorrow]. Recently, there was some backlash on the film “Aztec Batman: Clash of Empires”, which is actually a very cool movie. So this further inspires the need for these works.

Photo credit: Yvonne Tapia

YVONNE TAPIA: I agree, it’s so awesome and inspiring to highlight the beauty of past civilizations for a better understanding of what came to be today. A Batman with Aztec lineage? YES! Bring it haha.

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Haha, yes and it is fun! Got to work with other artists like Omar Chaparro.

YVONNE TAPIA: I know his comedic work, que padre! It’s a really wondrous moment when veteran artists work with new artists and uplift them in the mantel.

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Absolutely – y me encanta mi cultura, mis raices. Somos una gran variedad – Mixtecos, Mayas, etc.

YVONNE TAPIA: Igualmente, si es una alegria! The book’s artwork is beautiful as it highlights so much Aztec and modern Mexico’s environment; how did you develop it?

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: I’ve been drawing all of my life, my oldest memory is me drawing on the walls and filling in coloring books. Back in the day (laughs) we also used to write phone numbers or check them out through the “yellow pages” book. Very specific drawing memories were when my grandmother would give me a unique drawing proposition, to draw letters such as X or Y. She chose those since there aren’t a lot of words with those letters as starters, to make it challenging and get me to really think about what could inspire those less common letters. I would also draw characters like the Batman and The Joker.

Years later, I went to the university for graphic design while infusing my own knowledge of the culture. So when the book idea for A-Ztec: A Bilingual Alphabet Book came along, it was great and also a challenge because in Aztec vocabulary, some English-alphabet letters do not exist. For example, K or W. My editor was a huge help [inserting words for letters that do not exist in the Aztec alphabet].

Photo credit: Yvonne Tapia

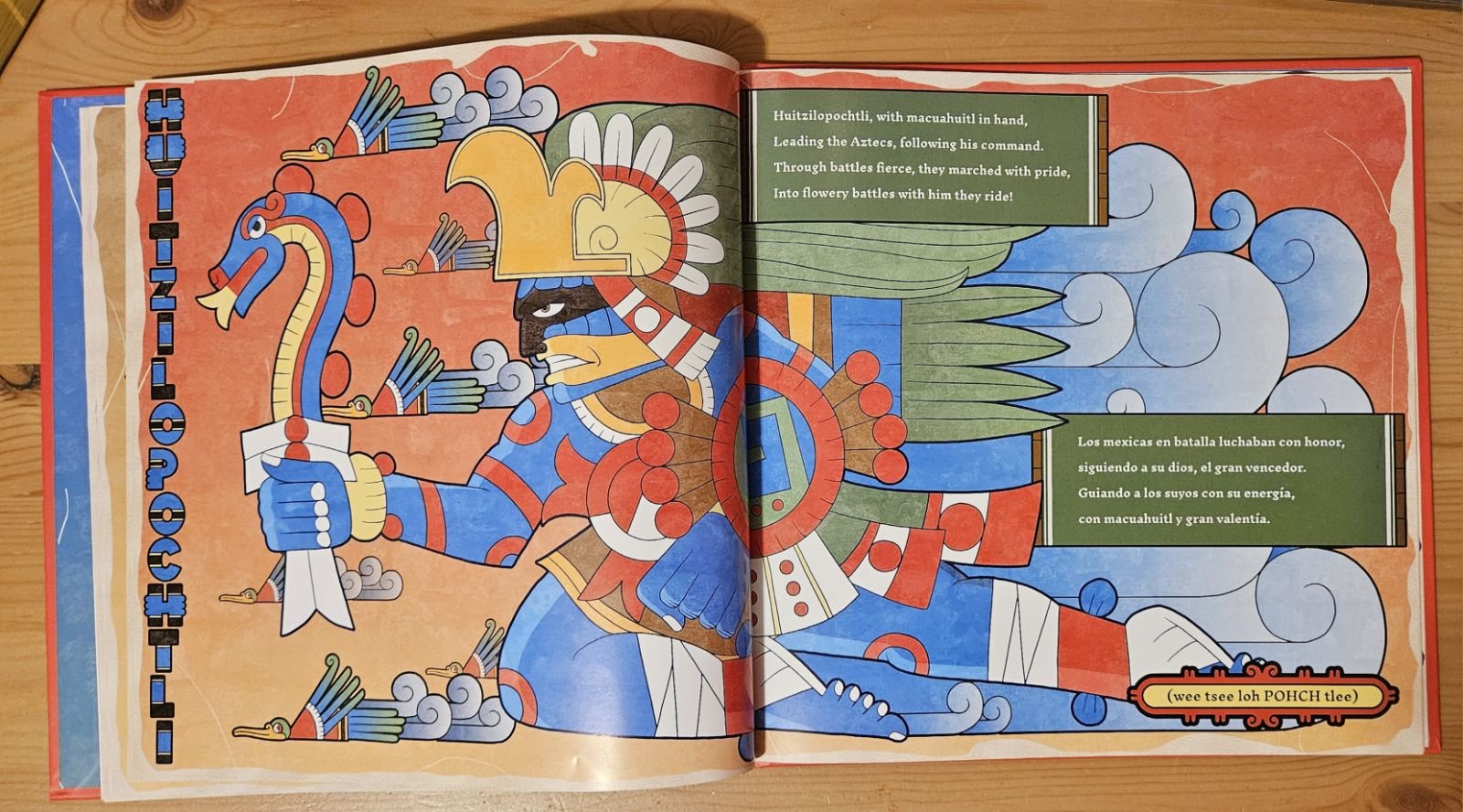

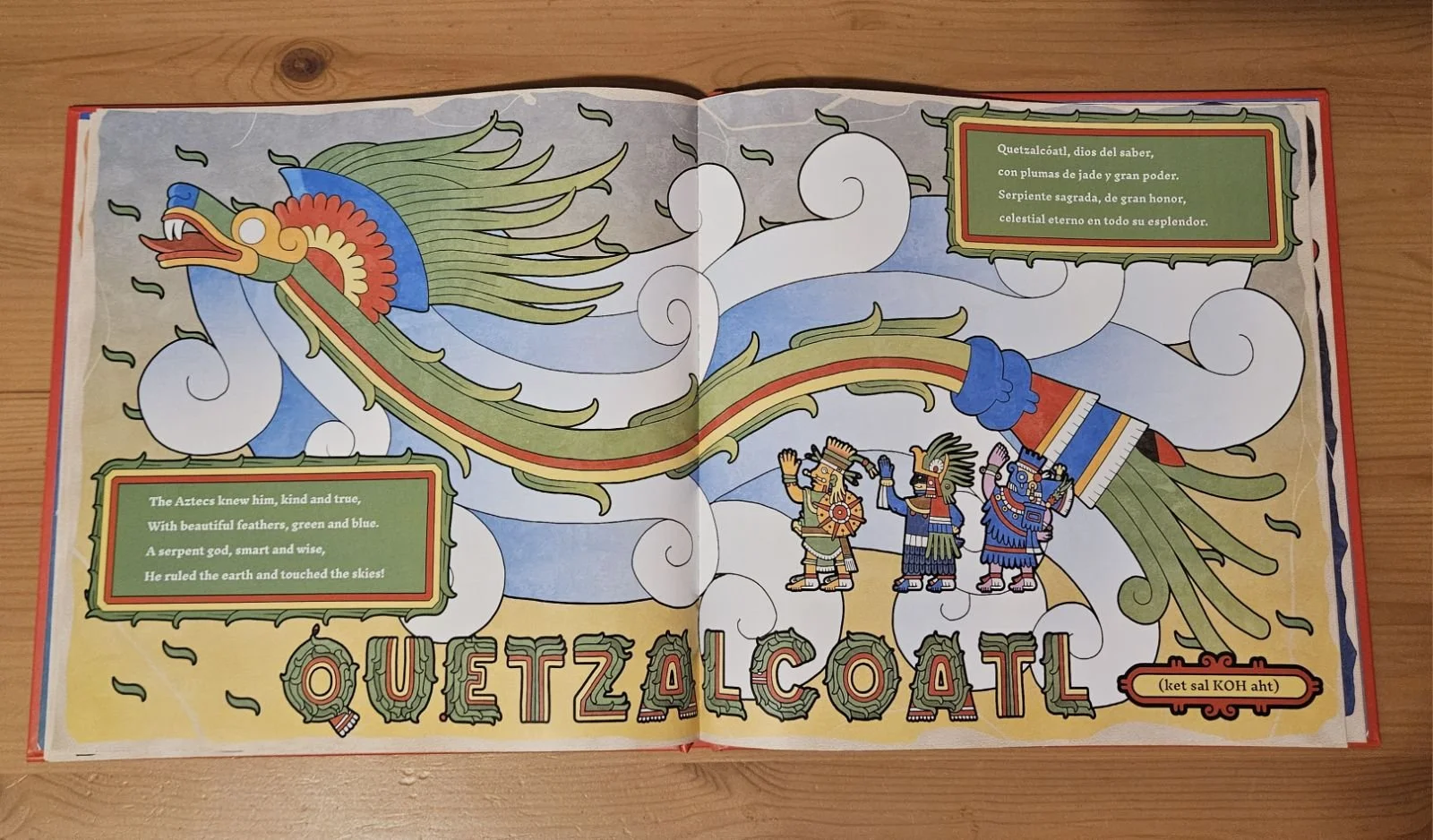

YVONNE TAPIA: I love to hear it! It’s essential to remember our roots and a lot of the vocabulary we use today originates from Nahuatl culture, like “chocolate” (xocolatl or chocolatl) and “elote” (elotl). You also include historical Aztec Gods, the artwork being so detailed, from the legendary feathered serpent, Quetzalcoatl to Huitzilopochtli. It’s beautiful! Each god represents something unique and connected to nature.

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: Thank you! Yep it is important to honor these wonderful masterpieces past civilizations provided.

YVONNE TAPIA: I second that! It was also great to see the wondrous pictionary included, glyphs specifically. It helps make learning something new even more fun.

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: It should be called Glyphonary haha. Yep, the Aztecs used glyphs to communicate in writing. Glyphs are symbols or images that represent different sounds, symbols, or concepts. It was beautiful to transfer that to this book.

Photo credit: Yvonne Tapia

YVONNE TAPIA:. What do you hope readers will get from this book?

EMMANUEL VALTIERRA: I hope they love the Aztec culture and share their reading excitement with family or friends. To enjoy reading about a different culture and setting. I want to bring something new and interesting to the table, for the [existing] and new generations – for them to discover something they might have never seen or heard before.

For more updates on his latest works: follow author and illustrator Emmanuel Valtierra on:

Website: https://emmanuelvaltierra.com/

Instagram: @emmanuelvaltierraillustrator

Publisher: Levine Querido

Mexican-American artist Emmanuel Valtierra studied Graphic Design in the University of Nuevo Leon (UANL) and Photography in San Antonio College. After some time, he adopted the aztec codex style for most of his works bringing him attention from the public and press. To stablish himself as a "tlacuilo", he released a series of pop culture images, playing cards, and book. All with Aztec style.

The love Valtierra has for history has influenced him on all his projects. The goal is to keep teaching new generations about our past in a fun way in every media possible.

Some of his most populare releases are: Codex Valtierra (sidewise award), Codice peregrino (white raven award), Aztec tarot, Blue beetle #1 (DC comics variant cover art),

Yvonne Tapia, a Mexican-American professional, has an extensive background in marketing, education, and media, supporting both large enterprises and small businesses. Yvonne focuses on raising brand visibility and community engagement, particularly within marginalized sectors. She currently serves as a Senior Instructor at COOP Careers, where she mentors through hands-on digital marketing training while partnering with businesses from different industries. Outside of work, Yvonne is an avid reader and is involved in supportive causes.