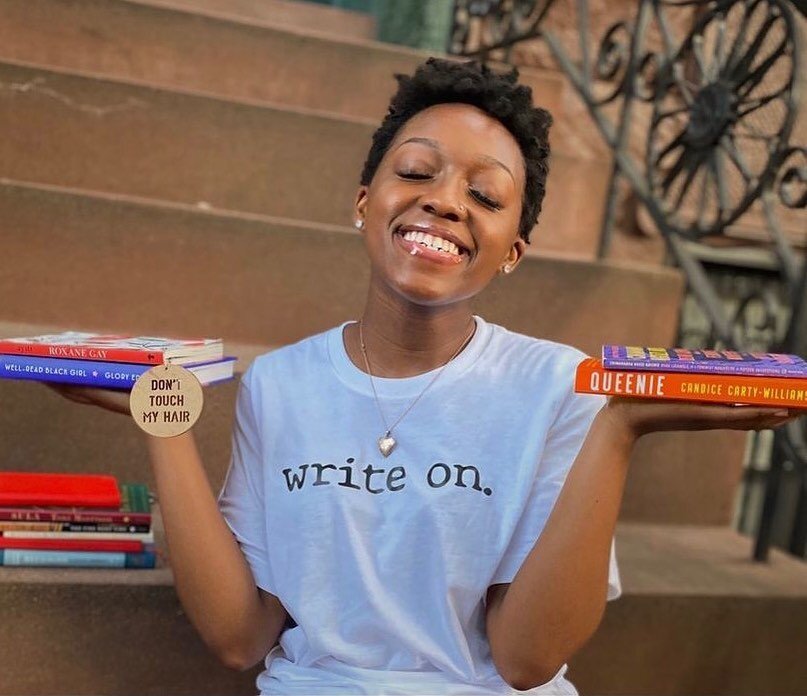

Writers Mentorship Program mentee Ayling Zulema Dominguez sat down with mentor Ariana Brown to discuss her poetry collection, We Are Owed. Continue reading for this insightful conversation and do not forget to grab your copy before the end of 2025!

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Ayling Zulema Dominguez (AZD): We Are Owed. is your debut poetry collection, and it is such a thorough work of confronting anti-Blackness in nationalist identities, as well as writing about Black kin in very venerative and beloved ways. How did you arrive at the core questions and investigations of We Are Owed.?

Ariana Brown (AB): I was kind of the resident Black History expert in Mexican-American Studies classes. Professors would refer to me for dates and times of certain events. And it was wild to me because I thought, “This department is in the same building as Black Studies; do y’all not talk to each other?” A lot of the questions in We Are Owed. come from that place of frustration. Of being someone who is able to recognize patterns, is unafraid to name them, and goes on to ask people, “Now that we know they exist, what are you going to do about that?” Because as someone who is racialized as Black in every space I enter, at least in this country, I don’t question who I am as a person, the world tells me—that’s what interpolation is, that’s what anti-Blackness is. So, I don’t have these questions of, “Who do I belong to?” Who I belong to is very clear to me. My question is, “How do we achieve liberation?” And I think that requires a certain precision and specificity that, if you are indoctrinated into the concepts of mestizaje and ‘we all have this indigenous past,’ I think can get really lost because you start to play around with the meanings of things, and I think that can get really dangerous. So in the collection, I really do insist on specificity. The meanings of things matter to me. Clarity matters to me.

(AZD): Was there any point in writing the book where there were obstacles to clarity, and if so, how did you approach that?

(AB): One of the experiences that I write about in We Are Owed. was a study abroad trip I did during college to Mexico City. I was the only Black person on the trip, everyone else in the group were mostly bilingual Mexican-Americans who had grown up in the border-towns along the Texas-Mexico border. Being in Mexico City really helped me figure out some of the specificity in We Are Owed., because I do think that if you are a child of immigrants or you exist in the diaspora somewhere and are not living in your ancestral homeland, there can be a tendency to essentialize and romanticize what the experience is of being someone in your homeland is, or what your identity is as a whole. Being in a space where most of my classmates were actually from South Texas, versus me being from San Antonio, I always thought San Antonio was South Texas until I heard my classmates from the valley say San Antonio is Central Texas, and I thought to myself, “Oh, they’re right. I don’t have a right to claim South Texas because living in a border-town is very different from living in a large metropolitan city in San Antonio.” It was important for me to be willing to acknowledge the differences in our experience, because in those moments, it wasn’t useful for me to say, “but we’re all Mexican.” For instance, their parents worked on the Mexico side of the border; they got paid in pesos. I had to be able to recognize, “Yes, I’m the only Black person on this trip, but I have class privilege at this moment because my mom gets paid in U.S. dollars, not in pesos.” Even being in Mexico City and just watching how all of us were racialized differently—most of my classmates would definitely be racialized as “Other” in the U.S., but in Mexico, they were called “gringas,” and they were very confused by this. To them, they were brown, and being called “gringa” felt like a rejection of who they were. But for the locals, they were just acknowledging that my classmates were not from there, and were American. So, there were all of these areas that people might think of as “gray areas,” but to me it felt very helpful to be able to see that clarity, because then I could make sense of things. A lot of the research for We Are Owed. was figuring out, “What are the stories we tell ourselves about who we are? Where did they come from, and what purpose do they serve?” And then trying to figure out what I want my relationship to these stories to be; do I find them helpful? Do I find them hurtful? What do I need to correct? What do I want to be clear about?

(AZD): In your poem, “At the End of the Borderlands,” you write, “would you fight for those you don’t love, to whom you are indebted?” There is such a palpable praxis of care woven into the book, and I was wondering if you could expand a bit on what it means to be indebted to whom we may not love?

(AB): There’s a book that I read while I was writing We Are Owed. called Research is Ceremony: Indigenous Research Methods by Shawn Wilson, and in the book he coins the term “relational accountability.” The term is part of ethnographic research and elaborates the idea of ‘nothing about us without us.’ This idea that we don’t exist apart from each other. One of the examples I can think of right now is the genocide happening in Palestine. Right now, it’s the week of the strike that Bisan called for, so I am striking. I don’t personally know people in Palestine, but I am indebted to them. I don’t have to love you to fight alongside you. I think that’s a really key part that a lot of folks are missing. Especially when we come into this idea of social justice through what we see on social media, where everyone feels like you have to be this big happy family, and we have to honor our differences; that is important, yes, but it’s also not necessary. This is something that we learn from disability justice, that people do not have to be loved or likable in order to be worthy of living livable lives. That clarity, that specificity of “I don’t need you to like me, and I don’t need to like you, but I can recognize regardless of what my relationship is to you, you have a right to exist, to not be displaced from your homeland. Especially if the country I live in is actively funding your displacement and your genocide, I have a responsibility to do something, to not just feel something about it, but to do something about it.” Otherwise, what am I writing any of this stuff for, you know?

(AZD): We Are Owed. challenges the notion of identities being tied to nation-states, and the imperial languages that helped form these nation-states, in fact calling for adversarial relationships with nation-states. In your poem “Negrita,” you write, “I fear you offer your heart to this language ... To survive here, mija, I work on the words, making a list of everything we are owed.” What do you think a language that is worthy of offering one’s heart to looks like, if there ever is one?

(AB): The quote that almost opened We Are Owed. was by the Nigerian Writer, Chinua Achebe, which is, "Let no one be fooled by the fact that we may write in English, for we intend to do unheard of things with it." It didn’t quite fit, but I just love that quote and think about it all the time. I do think that in a lot of non-Black communities, there’s this feeling of needing to learn one’s heritage language, or else being completely lost to it and to one’s culture. And there's a reality to that. But I also think, as an African-American person who has been displaced from whatever my heritage language is for many generations, I think that African-Americans and Black folks in diaspora show us constantly, time and time again, how we have made language our own, how we have made culture our own. When I was a little kid, I used to spend summers with my great grandmother in Galveston, TX, and we would go to church together. Being around Black Baptist preachers, that mode of communication and fellowship is so specific—how one relates to another person in that space, how you participate in that space, how language is used. There are so many different ways to communicate that are beyond the word itself. And when I think about language that is liberatory, it’s not necessarily something a matter of, “I need to find something that is completely removed from a colonial history,” but rather, why can’t that language be tenderness? Why can’t that language be me reaching out to you and us holding each other in this knowing that we are in the muck of it, but we’re gonna hold on to each other no matter what? For me, it’s less about the specific words that one uses. I think we waste a lot of time lamenting or trying to get back what was lost. I think that energy could be better directed towards a real politic of mutuality. I think that is where our future really really lies. I think that’s where all the potential is, in our relationships with one another. That to me is decolonial. That to me is anticolonial. Sometimes it doesn’t quite matter the words you use, sometimes the actions are the most important thing.