Discover Your Roots

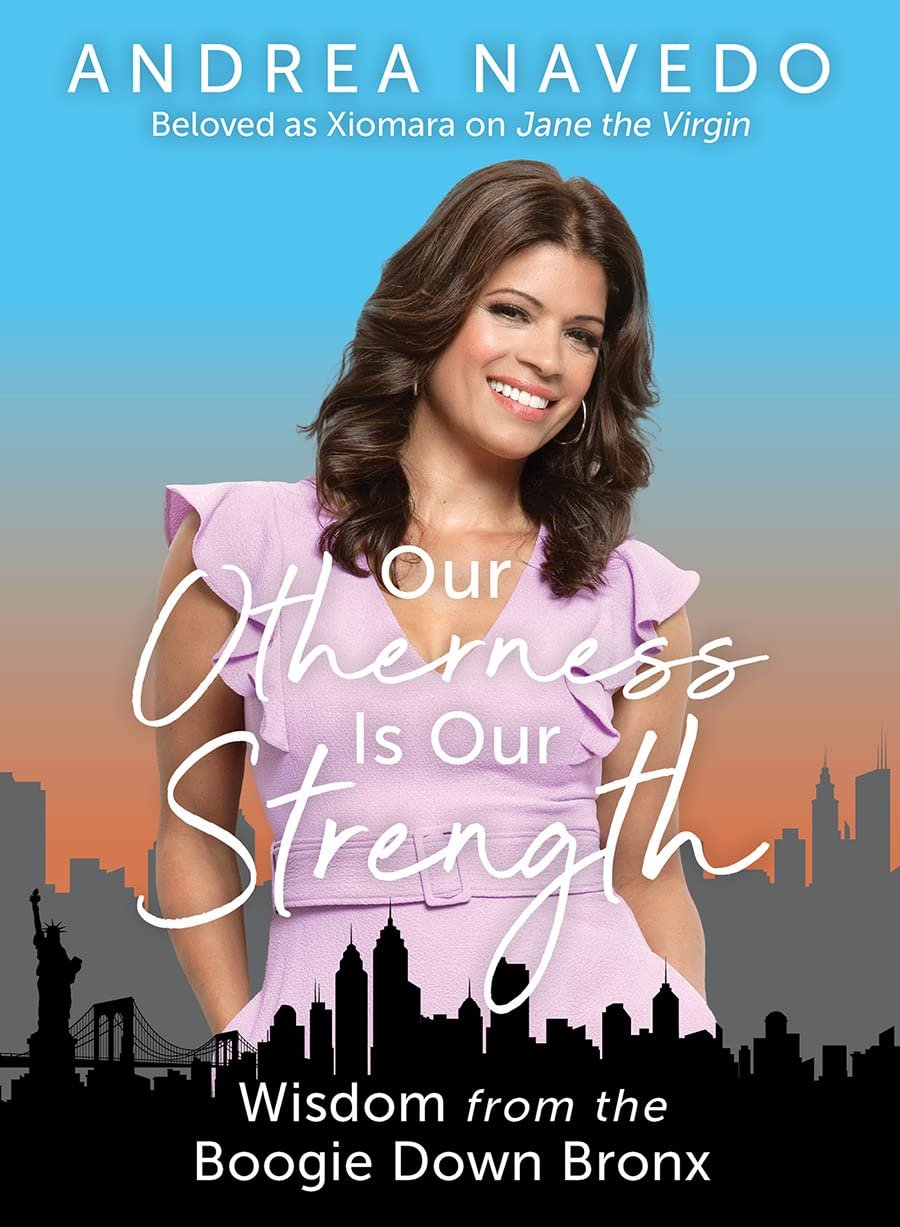

. . . when I was eleven my parents sent me to Puerto Rico to spend the summer with my other grandma, Grandma Benny. I went all by myself on a plane and I got to sit by the window! It was incredible to be in the air looking down at NYC, the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, and the towers of the World Trade Center. The city looked like a miniature toy set and everyone looked like ants. As we ascended, we eventually flew past a layer of white fluffy clouds and spent most of the flight above them. It was weird; it made the world feel upside down. I had never had this point of view before. As we flew, I gazed out of the window and imagined myself outside, jumping on top of those clouds, like on a trampoline, bouncing from one cloud to another or lazily lounging on top of one and ripping off a piece of fluffy cloud to eat like cotton candy. The stewardesses (that’s what we called them back then) were super sweet. They would check on me from time to time to see if I wanted or needed anything. They asked if I wanted to eat breakfast and one of the options was pancakes. Woohoo, had I died and gone to heaven? Of course, I wanted breakfast and yes, “I’ll have the pancakes please!” I was so excited. This trip to Puerto Rico was turning out to be great! Then—record scratch—the pancakes arrived and I disappointedly discovered what the term “airplane food” meant.

Three hours later, we approached the beautiful island of Borinquen. (I learned that Borinquen was what the original native inhabitants, the Taínos, called the island, before it was invaded by Spain. Hence why people from the island refer to themselves as Boricua.) Soaring above the lush tropical landscape, I caught my first glimpse of the calm turquoise waters of Puerto Rico. Wow! I had never seen water that color. Hugging along the coastline and cruising above the palm trees I could see why its other name was La Isla del Encanto (The Isle of Enchantment), because it was so beautiful.

Once off the plane I was escorted to the terminal to meet my grandmother. I had no idea how we were going to find her because I didn’t know what she looked like. The last time I had seen her was probably when I was a baby when she was still living in NYC. Eventually we found her, along with my step-grandfather and my teenage aunt Patti. It was weird meeting them. They were complete strangers to me. Grandma Benny was blonde and had blue eyes and looked like my father. I knew my father was Puerto Rican, with white skin, light brown hair, and blue eyes, but I thought he was an anomaly—adopted or something. All the other Hispanic people I knew were dark. But there she was, this white woman who spoke Spanish and who hugged me like I was her long-lost child. As she bear-hugged me, I flinched in pain because in between us, digging into my belly, was a gift for grandma that I held in my arms. It was from my dad, an old-fashioned wooden coffee grinder, the kind that has an ornately designed cast-iron wheel that needs to be manually operated to grind the coffee. Her eyes lit up. She seemed very pleased.

We finally arrived at her house. My grandmother proudly told me that she and her husband had built the house themselves. They had immigrated to New York years back and busted their asses working, with the plan to save enough money to move back to Puerto Rico and build a home. And that’s exactly what they did. It was a humble home but it was nice. The neighborhood smelled like fresh-baked bread and, in the distance, roosters crowed almost constantly. Hold up! Shut the front door! Roosters crowing? At this hour? It was the afternoon! What were they doing crowing during the day? Everyone knows that roosters crow at the crack of dawn to wake everyone up. Nature’s alarm clock. That’s what I learned watching Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on TV. TV was the original homeschooling if you were from the hood. We didn’t have roosters back in The Bronx. Mister Rogers said they crow at dawn. Head scratch. It got me thinking— Mister Rogers, a white man, could be wrong?

The house was situated in a suburb of San Juan with a weird-sounding name, Bayamòn. I learned that was another Indigenous name. I had only just arrived and was already learning so much. I learned that “airplane food” means “bad food,” that Puerto Rico was originally inhabited by an Indigenous people called Taínos who called the island Boriquen, that roosters crow any time of day, basically whenever they feel like it, that white people can speak Spanish, and white people don’t know everything or white people can be wrong. Interesting.

That evening Grandma Benny served the most amazing meal. One I will never forget. She made sancocho. She said it was my father’s favorite dish. Sancocho is a hearty stew made of tender chunks of beef, chicken, and/or pork, with root vegetables like yucca, sweet potato, plantains, and more. She served it along with white fluffy rice and slices of aguacate (avocado). It was the most flavorful, satisfying, and comforting meal I had ever had in my life. I felt like I had died and gone to heaven. Especially after that “airplane food” experience. I ate that sancocho like there was no tomorrow. I could see the pride and pleasure in my grandmother’s eyes as I devoured that stew. She loved watching me eat with such gusto. She didn’t take her eyes off of me. Finally, I came up for air. I was pretty full. I leaned back, put my spoon down, and opened the top button of my shorts. Well, the look that came over Grandma Benny’s face. Pleasure turned to a look of dismay in two seconds flat. Grandma Benny immediately picked up that spoon and started to feed me like a baby. She said kids were starving in China, and that I had to finish everything on my plate. She kept scooping and shoveling it into my mouth until that huge bowl was empty. I could barely move. I could literally feel the food at the top of my throat. I was afraid to move for fear of it coming out. I carefully, ever so carefully, got up, sat down on the couch, opened my shorts completely, and didn’t move for hours.

Grandma Benny had served me a man-size bowl of sancocho, probably the same amount she would’ve served my dad. I was very skinny, didn’t weigh more than seventy pounds, and I’m sure she was determined to get some fat on my bones before she sent me back home to NYC.

Like I mentioned, the neighborhood smelled like bread because a few blocks away was a panaderia—a bakery. The bakery made bread all day long and the smell in the area was intoxicating. My first morning, at 7 a.m., Grandma and I went to the bakery to buy a loaf of pan de agua or “water bread.” Pan de agua is a long loaf of white bread. It has a hard and crispy crust with a fluffy airy center. When we got home Grandma asked if I wanted breakfast. I enthusiastically said yes, having discovered this woman was a queen in the kitchen. Ten minutes later she called me to breakfast and placed in front of me a cup of café con leche (coffee with milk) and a slice of pan de agua with a slathering of butter in the center. I was amazed that she was serving me coffee. I thought only adults could have it. It made me feel grown up. I took a sip of the coffee and it was delicious, better than hot cocoa. I then excitedly took my first bite of pan de agua and nearly fell out of my chair in ecstasy. It was warm, crispy, tender, and literally melted in my mouth. I was enraptured. I basically inhaled it and immediately asked for seconds. Grandma Benny smiled, then served me another slice. I inhaled that one too and quickly asked for thirds. But this time she said no, a surprise since she seemed to derive such joy from shoveling food into my mouth. She said the rest of the bread was for Grandpa and Patti but, if I wanted, I could have a whole loaf to myself next time if I went by myself in the mornings to pick up the bread. Bet grandma, I’m down with that!

One day grandma’s brother stopped by the house in his pickup truck. He looked like the male version of Grandma Benny, but he had a somewhat weathered look. He looked strong, with broad shoulders and big calloused hands. He lived and worked on the family farm. I had no idea my family had a farm!

In the back of the truck were big burlap sacks filled to the top with beans. All kinds of beans—black, red, kidney, and coffee beans. He had come by to bring her some of the beans he had harvested. He proceeded to unload the sacks and put them on the patio. After some chitchat in Spanish he left and grandma turned to me and asked if I wanted a cup of coffee. Since arriving to Puerto Rico I had become a real coffee addict. The coffee grandma made was so so good! It was like dessert, so of course I said yes!

“Okay, entonces ayudame,” Grandma said. “Help me carry the coffee beans to the back patio.” She took an empty burlap sack, laid it out on the patio floor in the sun, and then proceeded to show me how to spread the beans out on top of it. “Okay, we need to let it bake in the sun. Go and play.” About a half hour went by and Grandma yelled for me to come back. I thought she was calling me for my café con leche, but no. Instead she showed me how to rake the coffee beans and then sent me away again. This went on for hours. Every thirty minutes or so we raked the beans. Every so often she would bite into one of them to see if they were ready and every time she would say, “No, not ready.” Finally, after what seemed like forever, she took one last bite and announced, “Ya, they are ready. Búscame el coffee grinder that your Papi bought for me.” I ran to fetch it and she told me to sit down, hold it in my lap, place coffee beans inside the cast iron bowl, and crank the handle. Within a few minutes we had freshly ground coffee inside of the wooden drawer at the bottom of the grinder. It was so cool! She then said, “Okay, now I will make your café con leche,” and went inside the house.

I patiently sat waiting on the patio until she finally came out with the most amazing cup of coffee. It was hot, but not too hot. It was the perfect color of light caramel with a sweet, creamy, deep, smooth, almost chocolaty taste. Again I was in taste-bud heaven. To this day I still haven’t been able to duplicate that cup of coffee. It was a once-in-a-lifetime, unforgettable experience.

That month in Puerto Rico was one of the highlights of my childhood. I learned so much about my identity as a Puertoriqueña. My parents had originally offered the trip as an incentive for me to do well in school. However, my grades still sucked by the end of the school year. I thought for sure I wasn’t going get to go to Puerto Rico for the summer. Thankfully my parents sent me anyway. They most likely figured it would be good for me. They were right because eleven-year-old me got to go to the island of Puerto Rico! Borinquen! La Isla del Encanto! And finally feel some sense of belonging.

Excerpted from "Our Otherness is Our Strength: Wisdom from the Boogie Down Bronx," used with permission from Broadleaf Books., www.broadleafbooks.com. (c) Andrea Navedo