Latinx in Publishing is pleased to exclusively reveal a chapter from Aloha Compadre: Latinxs in Hawaiʻi by Rudy P. Guevarra Jr.

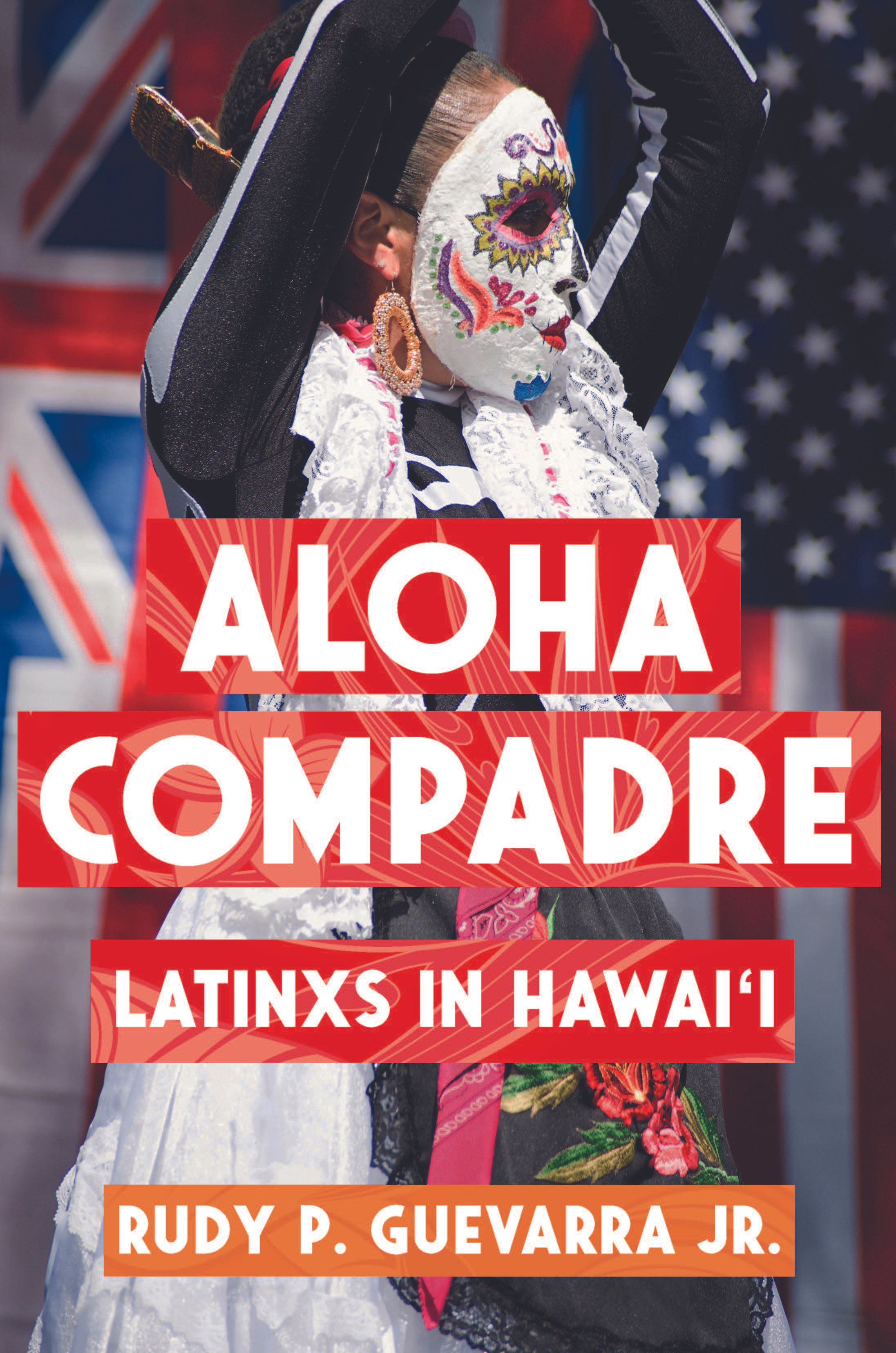

Aloha Compadre: Latinxs in Hawaiʻi is the first book to examine the collective history and contemporary experiences of the Latinx population of Hawaiʻi. This study reveals that contrary to popular discourse, Latinx migration to Hawaiʻi is not a recent event. In the national memory of the United States, for example, the Latinx population of Hawaiʻi is often portrayed as recent arrivals and not as long-term historical communities with a presence that precedes the formation of statehood itself. Historically speaking, Latinxs have been voyaging to the Hawaiian Islands for over one hundred and ninety years. From the early 1830s to the present, they continue to help shape Hawaiʻi’s history, yet their contributions are often overlooked. Latinxs have been a part of the cultural landscape of Hawaiʻi prior to annexation, territorial status, and statehood in 1959. Aloha Compadre also explores the expanding boundaries of Latinx migration beyond the western hemisphere and into Oceania.

INTRODUCTION:

The Deportation of

Andres Magaña Ortiz

On July 7, 2017, Andres Magaña Ortiz said goodbye to his wife and three children—all of whom are U.S. citizens—and boarded a flight bound for México, where he will remain separated from his family until he can be petitioned by his daughter Victoria to become a legal permanent resident. It is a process that could take up to ten years.1 Andres Magaña Ortiz is forty-three years old, a Mexican immigrant who has lived in the United States for nearly thirty years. His family, community, and life’s work are all in Hawaiʻi. In 1989, at the age of fifteen, he was smuggled across the Arizona-México border to reunite with his mother, who was working in California at the time. They eventually made their way to Hawaiʻi, where he picked coffee as a migrant laborer in Kona, on Hawaiʻi Island (Big Island).2 Within ten years he was able to save enough money to purchase six acres of farmland in Holualoa and begin his journey as a farm owner. He named his farm El Molinito (the mill), which had an old Japanese-style coffee mill that he began renovating in 2008.3 According to the Washington Post, in the years that followed, Magaña Ortiz “rose to prominence in Hawaiʻi’s coffee industry. In 2010, he allowed the US Department of Agriculture to use his farm without charge to conduct a five-year study into a destructive insect species harming Hawaiʻi’s coffee crops.” After that, he was the most sought-after coffee grower for his expertise in ridding coffee farms in Kona and other areas of Hawaiʻi Island of 98 percent of the destructive borer beetles.4

In addition, Magaña Ortiz was also responsible for managing over one hundred acres of land among fifteen other small farmers, which included the elderly and those who were inexperienced and could not do the work on their own.5 His dream of continuing to live in Hawaiʻi was short lived, however. In 2011, under the Obama administration, the Department of Homeland Security began removal proceedings against Magaña Ortiz.6 He was informed that he would be deported to México, a place he is simply no longer familiar with. In response, Magaña Ortiz petitioned for legal residency and was granted multiple stays, yet his most recent request to gain legal residency was rejected by the Trump administration. Under the guise of cracking down on immigration, the Department of Homeland Security ordered Magaña Ortiz to leave in March 2017.7 It did not matter that he already had petitioned for legal residency as the husband of a U.S. citizen—he had to go. As Magaña Ortiz noted, “I never tried to hide it. I always answered my phone when immigration called me and said come see us. . . . I come to each court on time. Everything, I tried to do all my best.”8 Given that Magaña Ortiz was a well-known and respected member of the community and a leader of Hawaiʻi’s coffee industry, his case made national headlines.

A team of attorneys assisted Magaña Ortiz by filing last-minute petitions to grant him more time in the United States. Even Hawaiʻi’s congressional delegation supported his case, speaking on his behalf to Homeland Security secretary John F. Kelly to halt his removal. As the four-member delegation wrote, “He is trying to do the right thing.”9 In addition, representative and onetime presidential candidate Tulsi Gabbard introduced a bill to make Magaña Ortiz eligible for legal, permanent residency. Senator Mazie Hirono also spoke on Magaña Ortiz’s behalf, stating, “Andres’ ordeal speaks to the very real fear and anxiety spreading through immigrant communities across the country.”10

Federal appeals court judges also supported Magaña Ortiz’s case, calling him a “pillar of his community” and criticizing the Trump administration handling of his case. For example, Judge Stephen Reinhardt of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit called Magaña Ortiz’s deportation “contrary to the values of the country and its legal system. . . . The government decision to remove Magaña Ortiz diminishes not only our country but our courts, which are supposedly dedicated to the pursuit of justice.”11 Despite having a strong case, the inhospitable climate proved too much. Magaña Ortiz decided to depart voluntarily ahead of the deportation order. When interviewed by Hawaii News Now at Kona International Airport during his departure, he regarded the circumstances of his case: “Very, very sad and very disappointed in many ways, but there’s not much I can do. . . . Just follow what I have to do and hopefully, in a little bit, things can get better.”12

His family has fared no better because of this. Magaña Ortiz’s eldest daughter, Victoria, almost had to withdraw from college at the University of Hawaiʻi to help support the family as they struggled to keep their father’s business afloat.13 She graduated a little later than expected but was able to finish her education online. As Victoria noted about this sudden responsibility for managing the family business,

I think I would have liked to have my own business when I created it. You slowly go with it, but the thing was running and going full speed, and I didn’t know what the heck I was doing. So I think that was the pressure. My dad is now deported. My mom has had back surgery; she’s injured, so she doesn’t work. I have my brother and my sister, so I have all four of them on my plate all of a sudden. And my dad had always been the one to solve problems. My mom was always like, “We have a dentist appointment. Fill out these forms for me.” Normal Hispanic child, right? And my dad was always the one that I used to run to when I had issues. And suddenly my safety net is just gone. So I think it was really hard for me when that happened because suddenly I was the one to make the decisions and have all the responsibilities.14

Andres Magaña Ortiz’s journey took him to the municipal city of Morelia, México, to a village called El Rincon de Don Pedro, Michoacán, where he had once lived before coming to the United States. Magaña Ortiz will remain in México until he is reunited with his family back in Hawaiʻi, a place they consider home. As Magaña Ortiz shared before he left, “I love this country and I love these islands. If I have to leave, it’s going to be hard on everyone.”15 The separation of Andres from his wife and children left them with an urgent sense of fear and uncertainty. They said their goodbyes at home so that the younger children did not have to go to the airport and be further subjected to the trauma of seeing their father leave. For Victoria, it was all surreal. She shared, “After so much fight that we went through, for it to just end like this. I mean, it’s not necessarily the ending, but it is hard to see him go.” She added, “We’re still fighting to get him back here.”16

Political Context in Contemporary Hawaiʻi

Andres Magaña Ortiz’s story and that of his family speak to the current political situation around immigration in Hawaiʻi and across the continental United States. What makes his story both powerful and tragic is that Magaña Ortiz was not the exaggerated racial stereotype of a “criminal” that Trump had suggested was invading the United States. Rather, he was a husband, father, and business owner who contributed to the social and economic prosperity of Hawaiʻi’s Kona coffee industry. Andres’s daughter Victoria was also disheartened at how her father was categorized as a criminal and deported because of a previous charge of driving under the influence (DUI). Under the law, his DUI was enough to start deportation proceedings, despite having an exemplary record as a long-time resident of Hawaiʻi. Victoria remarked, “If my dad, being so loved here and being a workaholic and he’s still justified as a criminal for a mistake that he did, who else are you putting into these things [categories]? Are they getting traffic tickets? They’re not supposed to just take your life away like that.”17

Despite the outpouring of legal and political support in Hawaiʻi and the aloha (love and inclusion) Magaña Ortiz received from the various communities mentioned, under the Trump administration, he was ordered to leave. There was no consideration of the benefit his contributions were making to the state and his local community. Rather, because he is Mexican and undocumented—not by his choice—and subject to the racism of the justice system, he was forcibly removed from his family, friends, and longtime home to a place he no longer knows.18 His story reminds us of how poorly the United States has treated its citizens, whether legally documented or not. It is likely there were many conservative settlers in Hawaiʻi who applauded his deportation because they deem Latinx people a threat. However, there was a huge outpouring of support and aloha from the larger community who understood the humanity of his case and sought to support Magaña Ortiz through calls, petitions, and other means. Although he had to leave Hawaiʻi, his story and legacy resonate with me in terms of what it means to be Latinx in Hawaiʻi today in a national climate of increasing xenophobia and racism toward immigrants. I say this as someone who has been privileged to come to Hawaiʻi for more than twenty years, spending that time living, building intimate ties with the Latinx communities, and nurturing my existing networks of hānai and chosen family, friends, and colleagues who identify as Native Hawaiian, local, haole, and/or transplants to the islands. My observations reveal that although Hawaiʻi has long been a place known for its aloha, this seminal Hawaiian concept is being tested by the growing racist, xenophobic tide that is washing upon Hawaiʻi’s shores from outsiders, both haole and non-Native settlers.19

It is here that I turn to what Magaña Ortiz’s story represents to the larger Latinx community in Hawaiʻi, which has been the growing xenophobia and racism that is being fueled by the larger national climate through popular discourse in the media, writers, pundits, scholars, and politicians. This sentiment reveals the ever-present tension in Hawaiʻi that is now more visible because of the infectious nature of racism and white supremacy. At the same time, I am also mindful of the ways that Kānaka Maoli continue to be dispossessed and displaced from their homeland within a settler colonial system. They must also be included in this conversation, since Latinx migration is made possible through the suppression of Native Hawaiian self-governance. Seen by most residents as recent migrants or newcomers, the Latinx population of Hawaiʻi is increasing in numbers, but that growth is also hidden in plain sight. Due in part to Hawaiʻi’s already historically mixed population that also includes Pacific Islanders and Asians among other racial and ethnic groups, the Latinx population is often mistaken as “local” in Hawaiʻi depending on the context.20

Though increasing with new migrations, the Latinx population is not new to the Hawaiian Islands. On the contrary, Latinxs have been voyaging to the Hawaiian archipelago for 190 years, yet their presence has been rendered invisible by the tourist industry and within the larger local population. Aloha Compadre demonstrates what historian Evelyn Hu-DeHart also notes about Asians in Latin America, that these histories are hidden in plain view. There is no single, monolithic story to explain migration, and Latinx movements to Hawaiʻi and the larger Pacific region are as varied as the cultures that fall under the umbrella term Latinx.21 A small but steady flow of migration has occurred since the early 1830s; this has been both interrupted at times and inconsistent. Their roots, however, remain, as they were part of the first groups of foreigners who came during the reign of the Kamehamehas.22

As the first full-length study of the Latinx population in Hawaiʻi, in Aloha Compadre I offer the following: (1) I reveal how the Latinx population of Hawaiʻi is not a new phenomenon but a 190-plus-year journey of migration and intercultural community and identity building; (2) I expand our notion of how we understand and view la frontera (the borderlands) to include the ocean as a site of movement beyond terrestrial regions, which challenges us to see the continuous diaspora of Latinxs that spans globally across oceanic spaces; and (3) I explore how the Latinx population in Hawaiʻi has experienced both acceptance and aloha in their new home and also racism and “being racialized” in a climate that is increasingly becoming xenophobic. And precisely within this context, I explore how their acceptance or marginalization has occurred from the independent Hawaiian Kingdom to the twenty-first century, which seems to be contingent on their contributions, including but not limited to economic and cultural ones. My project analyzes how these experiences complicate the dominant narrative of Hawaiʻi as a multiracial utopia, an image shaped by early and contemporary writers who visited the islands. Aloha Compadre also documents the changing political climate in Hawaiʻi up to the early twenty-first century and how the Latinx population navigates the current tides of immigration policies, racism and xenophobia, and interracial relationships as they seek to build their communities and find a sense of belonging in the diaspora.

This is the story of the predominantly Spanish-speaking Latinx communities of Hawaiʻi and the social, political, and economic forces that influenced their migration thousands of miles across the Pacific for nearly two centuries. Similar to what anthropologist Sara V. Komarnisky has documented about the historical migrations of Mexicans to Alaska, the same can be said of Latinx migrations to Hawaiʻi in that “in some cases, the process of putting down roots requires mobility.”23 It is why there is both a large and rising Latinx population in Hawaiʻi. Rather than focus on a continual historic-to-contemporary timeline of migration and community formation, I will focus on four pivotal moments when the Latinx population came to Hawaiʻi, from the era of the independent Hawaiian Kingdom in the 1830s to the early 2000s. These four pivotal moments all center on the labor of specific Latinx communities throughout the islands: (1) Mexicans in the 1830s, (2) Puerto Ricans in the early 1900s, (3) Mexicans and Central Americans in the 1990s, and (4) Mexicans and Central Americans in the early 2000s. I suggest that Latinx migration in these four moments was vital to the continuing legacy of specific industries in Hawaiʻi, including cattle ranching, sugar cane, pineapple, Kona coffee, and macadamia nuts. Indeed, the need for labor was one of the primary reasons Latinxs came to Hawaiʻi, but it did not define them as such. Others came as small business owners, students, or the military.

While labor was the impetus for Latinx migrations in these episodic moments, I look at the lives of my Latinx interviewees using a more complex approach to demonstrate that they are more than just workers.24 I focus on the stories I uncovered while doing archival and ethnographic research and the oral testimonies of individuals who were gracious enough to share their stories with me. Their stories are central to this study and bring to life the human element of these moments. For me, it is important to hear the stories of those who labored in these industries, humanize them, and examine how they adapted to their new home and found ways to develop their identities and communities in the diaspora within a Pacific Island context. Their stories illustrate the hopes, dreams, disappointments, and challenges of the Latinx population by providing insight into what we can learn about migration, adaptation and belonging, and cultural multiplicity in Hawaiʻi. These stories also provide meaningful interpretations of historical events from the perspectives of those who lived through them. They help us understand why those moments mattered to both the interviewees and historical figures who left behind a written record.

Excerpted from "Aloha Compadre: Latinxs in Hawaiʻi," used with permission from Rutgers University Press., www.rutgersuniversitypress.org. (c) Rudy P. Guevarra Jr.

RUDY P. GUEVARRA JR. is professor of Asian Pacific American studies in the School of Social Transformation at Arizona State University. He is the author of Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego (Rutgers University Press), and coeditor of Beyond Ethnicity: New Politics of Race in Hawaiʻi.