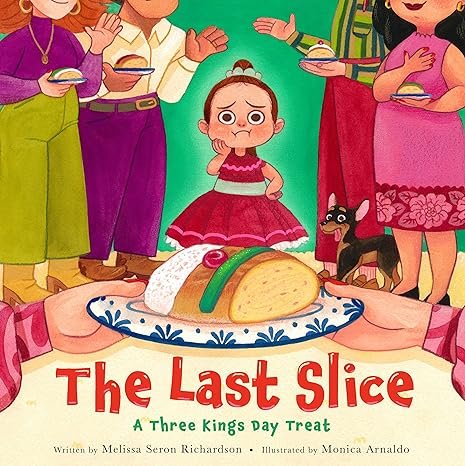

Water days are special days for a young girl in Trinidad—a town in central Cuba. They hold great significance for her whole village, actually.

On this particular water day, the girl joins her mami on a mission to mend their family’s leaky hose.

By the time the water man

finally arrives, we’ll be ready to fill

the blue tank on our flat red roof

with clear water

that flows

like hope

for my whole

thirsty familia.

Newbery Honor Award-winning author Margarita Engle brings readers Water Day—a celebratory picture book about the arrival of the water man to a small village. The book (out now from Atheneum Books for Young Readers) was illustrated by Olivia Sua.

The village in Water Day no longer has its own water supply. So residents rely on the water man, who visits weekly to distribute water to them. This time, he arrives in a wagon pulled by a horse that strains against the weight of a metal tank. Through the eyes of the book’s young narrator, readers are pulled into the anticipation of this day and, most importantly, what it means to have access to water.

“This story is really the contrast between how easy it is to get a drink of water in so many places, and how difficult it is in so many other places,” Engle told Latinx in Publishing. “And I’m not going to say that it’s just the U.S. against developing countries, because I live in a part of California where a lot of my neighbors’ wells have gone dry. And we don’t have access to city water because we’re in a rural residential zone. So if our wells go dry, that’s it. We have to do exactly what’s shown in this book, which is [to] bring water in a tanker truck.”

Engle was born in Los Angeles but spent many childhood summers with family in her mother’s hometown of Trinidad de Cuba. The author said she featured a horse and wagon for water transport in her book because, in Cuba, there’s a fuel shortage which causes horses to be used in some areas to bring water to people.

The joyous tone of Water Day is not only a credit to Engle’s lyrical style of writing, but also to Sua’s gorgeous illustrations. Sua’s art form of mostly painted cut paper breathes life into the book—bringing readers closer to Cuba and its people. There are also colorful houses with intricate iron window bars. There is a kitchen with hanging pots. A mango tree. There are mountain landscapes behind homes and churches. And even tinajones—big clay jars that the narrator’s great-grandmother says used to be filled with daily afternoon rains.

“This is probably one of the most research-intensive books I’ve ever done because I was trying to capture Trinidad,” Sua said. “I wanted to get the essence right.”

Though Water Day doesn’t explicitly say the story is set in Cuba, Engle confirmed it is.

Sua said she conducted a lot of research on Cuba through Google Maps and through photos of the country online. She also received input from Engle.

The illustrator said the story’s themes of environmentalism and the climate crisis first drew her to Engle’s manuscript. They are topics she cares deeply about.

Readers of Water Day may feel a jolt of realization as to just how important water is in their everyday lives. This is succinctly described in the below lines from the book:

Five days have passed

since the water man’s last visit.

We need to bathe,

wash clothes,

cook rice…

Engle didn’t hesitate when asked if that was intentional on her part.

“Yes, absolutely,” the author said. “We take water for granted. . . There’s a lot of injustice all over the world. It’s not just Cuba. It’s not just certain societies. There’s just this injustice in terms of access to water, and it’s so basic. This is something that everybody needs, but we don’t have equal access.”

Sua said Water Day is an important story. “Some of us are experiencing flooding,” the illustrator said, “and some of us are experiencing water scarcity.”

Engle has written many verse novels, memoirs, and picture books throughout her publishing career. For this book, she wanted to tell the story from the point of view of a child without scaring readers or making them sad.

“I actually wanted to focus on the joy of the arrival of the water, rather than on those days in between when you don’t have it being delivered,” the award-winning poet said. “I wanted to focus on the excitement of just what it means to finally have water.”

In her author’s note, Engle wrote about her mother’s hometown of Trinidad and how water access has become a lot more complicated due to factors such as climate change, polluted groundwater, and crumbling pipes for delivery. She told Latinx in Publishing that, when searching online for photos of the rooftops in Trinidad, you’ll see the blue tanks of water. You would not have seen that a few years ago, Engle added, “because everybody was able to get enough water from wells and so forth.”

She wants children to think about how privileged they are when they do have running water.

“I want to say we’re wealthy if we have that, but it’s a different kind of wealth because there are areas where middle-class people in the U.S. don’t have access to clean water,” Engle said. “So it’s just something to not take for granted. We need to treasure our natural resources.”

Margarita Engle is the Cuban American author of many books including the verse novels Rima’s Rebellion; Your Heart, My Sky; With a Star in My Hand; The Surrender Tree, a Newbery Honor winner; and The Lightning Dreamer. Her verse memoirs include Soaring Earth and Enchanted Air, which received the Pura Belpré Award, a Walter Dean Myers Award Honor, and was a finalist for the YALSA Award for Excellence in Nonfiction, among others. Her picture books include Drum Dream Girl, Dancing Hands, and The Flying Girl. Visit her at MargaritaEngle.com.

Olivia Sua is an artist who creates elaborate works of painted cut paper. She is from Washington State and resides in her hometown of North Bend. In 2020, Olivia graduated from Pacific Northwest College of Art with a BFA in illustration. When she’s not illustrating, Olivia likes to go backpacking, quilt, and collect seeds for her garden. Visit her at oliviasua.com.

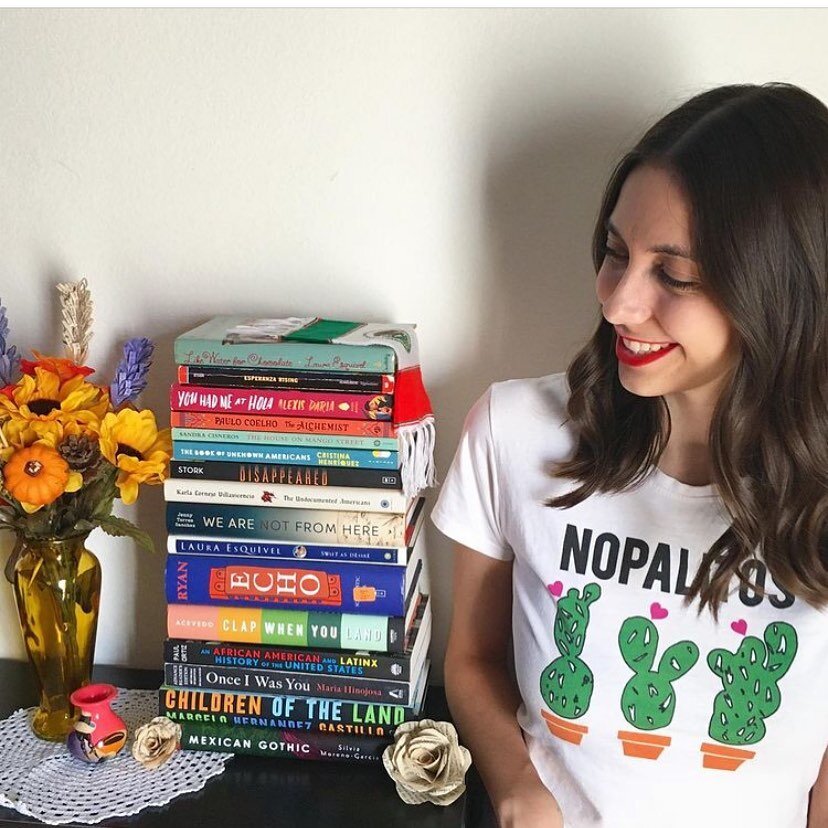

Amaris Castillo is an award-winning journalist, writer, and the creator of Bodega Stories, a series featuring real stories from the corner store. Her writing has appeared in La Galería Magazine, Aster(ix) Journal, Spanglish Voces, PALABRITAS, Dominican Moms Be Like… (part of the Dominican Writers Association’s #DWACuenticos chapbook series), and most recently Quislaona: A Dominican Fantasy Anthology and Sana, Sana: Latinx Pain and Radical Visions for Healing and Justice. Her short story, “El Don,” was a prize finalist for the 2022 Elizabeth Nunez Caribbean-American Writers’ Prize by the Brooklyn Caribbean Literary Festival. She is a proud member of Latinx in Publishing’s Writers Mentorship Class of 2023 and lives in Florida with her family and dog, Brooklyn.