For me, growing up I didn’t hear about a lot of the experiences of my family when they were in Cuba. They didn’t talk about them. One of the reasons I wrote Cuba in My Pocket was because I wanted to hear those stories. A lot of times there’s kind of a disconnect, where you don’t have all the family history that a lot of other families do. My husband’s family is from rural Oklahoma and when his grandfather passed away, they had this shed full of all this stuff from generations and generations past that was connected to their family history. Everything had a story. And I thought, I don’t have anything like that. I have things from my dad, but they’re all from things once he moved to the U.S. I have one small jewelry box that my grandmother actually wrote on the inside, “I brought this from Cuba.” That is literally the only thing.

So that’s a long-winded answer to say I was drawing from my own experience of kids that feel like they’re wanting that connection, perhaps—or maybe they don’t—with their family’s culture. But they’re not quite sure how that works. Then, of course, I wanted to throw in some horror just to make it fun—because I can never help that.

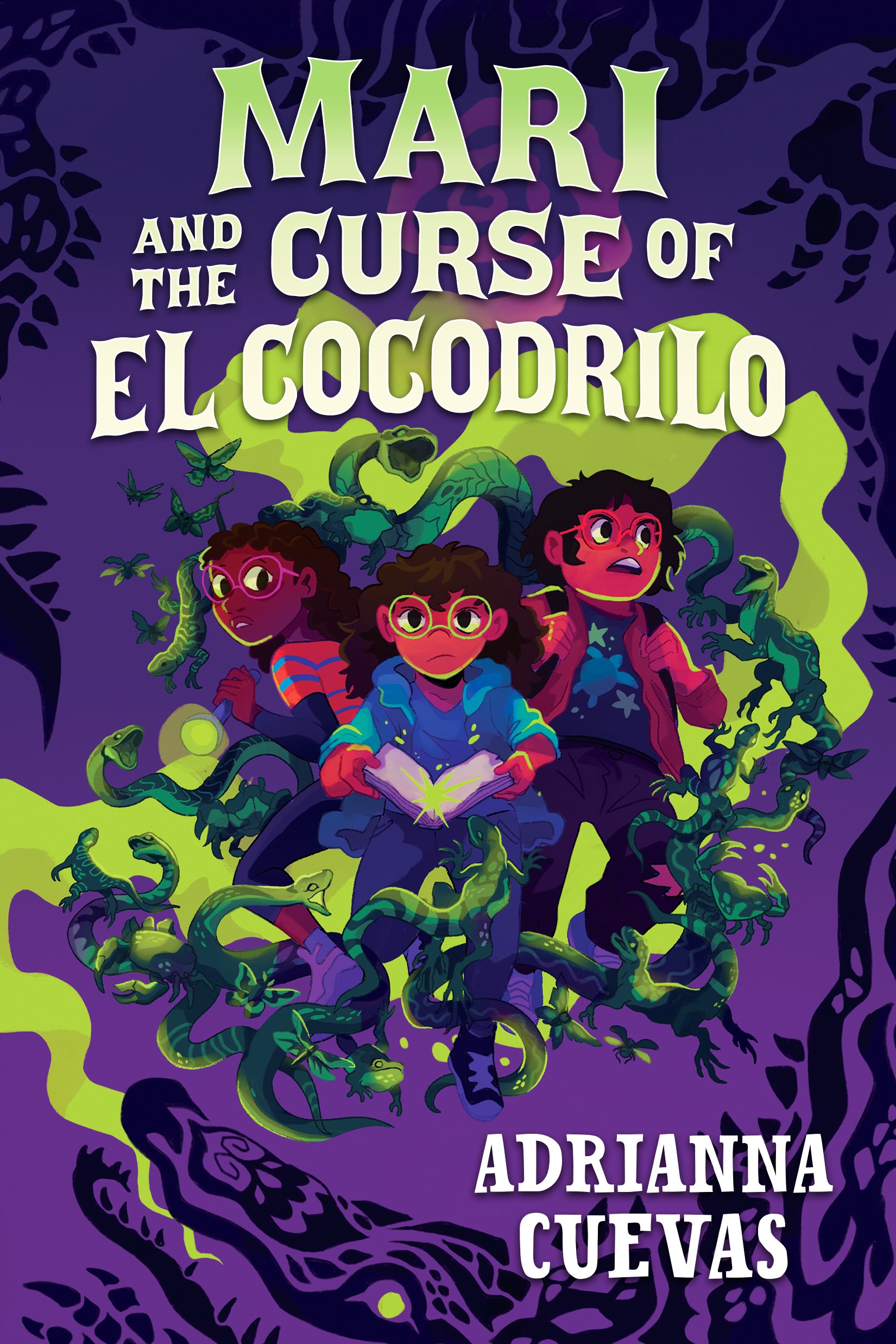

AC: Your main character, Maricela—or Mari—cringes at how extra her Cuban family can be. She even has a term for it: Peak Cubanity. It reminded me of how some first generation Americans struggle at times to straddle two cultures—that of the United States and of the country their parents hail from. What was it like crafting this character who, from the first page, seems to shun her family’s culture at first?

AC: A lot of it was not entirely based on my own experiences, but drawn from them. I grew up in Miami, Florida. Growing up Cuban in Miami, Florida, is a super privileged thing to do in all honesty, because your culture is everywhere. Our music is on the radio. You have your choice of Cuban restaurants to visit. You would go out and do all your errands for the day, and never have to speak English once.

I did not feel that sense of ‘other’ until I went to college in Missouri, because that was my first time being away from an area where, in all honesty, my culture was the majority. And so I got that sense that Mari does, of ‘Well, who am I and how do I fit in? And everyone here assumes that I’m Mexican because I speak Spanish.’ That happened to me a ton. It especially happens to me here in Texas. And so I wanted to honor those kids who feel the same way. I mean, Mari loves her family. But what child of any cultural background is not embarrassed by their family ever so often?

I wanted Mari to experience the joy that you can get from learning your family’s history, but at the same time understanding maybe why you didn’t know all about it to begin with. Because a lot of it can be painful. That happened when I was researching Cuba in My Pocket. I’m asking my dad and my cousins, as well, of their experiences in Cuba and coming over to the U.S. And not all the stories are great. You can see why maybe kids don’t hear everything, and adults are reluctant to talk about it. A lot of it was drawn from my personal experiences. But if you’ve ever met Cubans, the “Peak Cubanity” fits because we are not a subtle people. And so I had a lot of fun just writing the joy and the extra that Mari’s family is.

AC: Your book is so lively with all the bad luck shenanigans that happen to Mari and, later, her friend, Kiesha. How did you come up with all the bad luck instances that happen? That was so fun to read.

AC: I will say that coming up with nonsense or just off-the-wall things is not hard for me when I am living with a now 16-year-old. Neither he—as my son—nor I have any filters. We tend to bounce really silly ideas off of each other all the time. I think as a creative person, it is really important to have someone like that in your life who doesn’t edit your creativity. They encourage you.

In all honesty, I’ve gotten into the habit where, if an idea pops into my head—even if it’s really off-the-wall—I’m not self-editing right away. I think that happens to a lot of authors, where you come up with an idea and the very next spot is, ‘Oh, no, that’s dumb. Nobody’s gonna want to read that.’ Because I have people in my life—my husband, my son—who are always encouraging my ideas and helping me brainstorm even the most nonsensical thing, I really value that as somebody in a creative profession.

It’s not hard to think of off-the-wall things when you’re just kind of letting your brain go. I always joke that as a Cuban, it’s very easy to write horror. It’s very easy to write a character that’s been cursed with bad luck. By and large, because of our political history, Cubans tend to be pessimists in all honesty. They’re gonna look at a situation and pretty much assume the worst is going to happen. That’s the whole function of horror, is asking, ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ And so I feel like I was at a cultural advantage, thinking: ‘Well, what’s the worst that can happen to Mari in this situation?’

AC: You’re like, ‘I got this. I’m Cuban.’

AC: Exactly. Like, I was already being a pessimist about this situation. I knew what was going to happen.

AC: There’s another storyline here about the importance of documenting the stories and memories of family members who are deceased. What message were you hoping to send by highlighting this?

AC: I realize that for each of my books, it’s really my way of hanging on to something that I think is important, and that I think needs to be remembered. . . In Mari’s story, it’s my way of showing that, ‘This is why that’s important. We’re not going to have all these people around forever.’ You know, Mari only gets a lot of the stories from ghosts. We can’t let that be our option, where we’ve waited too long to preserve our family’s history.

One of the things that I am passionate about is the ability to tell our own stories, before someone else tells them for us. We need to remember and commemorate what’s happened to us before somebody else decides to tell our own history. And so I think that’s something I’m pretty passionate about because it’s now come up in pretty much every single manuscript I’ve written. I always have the adventure plot, the horror, the silliness, whatever—but the emotional core of all my stories is always going to come from something that I feel is important to remember. I think that’s why I addressed the story the way I did.

AC: What are you hoping readers take away from Mari and the Curse of El Cocodrilo?

AC: I never go into writing any of my books with a lesson in mind. Because, for me, I want young readers to dive into one of my books. I want them to lose track of time. I want them to forget where they are, and I want them to just enjoy a story. That’s my primary goal with every single one of my books.

With Mari though, it would make me pretty happy if it made a young reader curious about their own family’s histories, start asking their elders some questions, or asking to be told stories. But by and large, I’m always just wanting my readers to have fun with my books.